Braden and I write FatherSonBirding in the hopes of sharing the wonders of birds and birding, and the urgency to protect them. We do not accept advertising or donations, but if you’d like to support our work, please consider buying *NEW* copies of some of Sneed’s books—First-Time Japan, for instance, or my recent Orbis Pictus Award winner, Border Crossings. We appreciate your interest and hope you will keep reading! Happy Earth Day + 1!

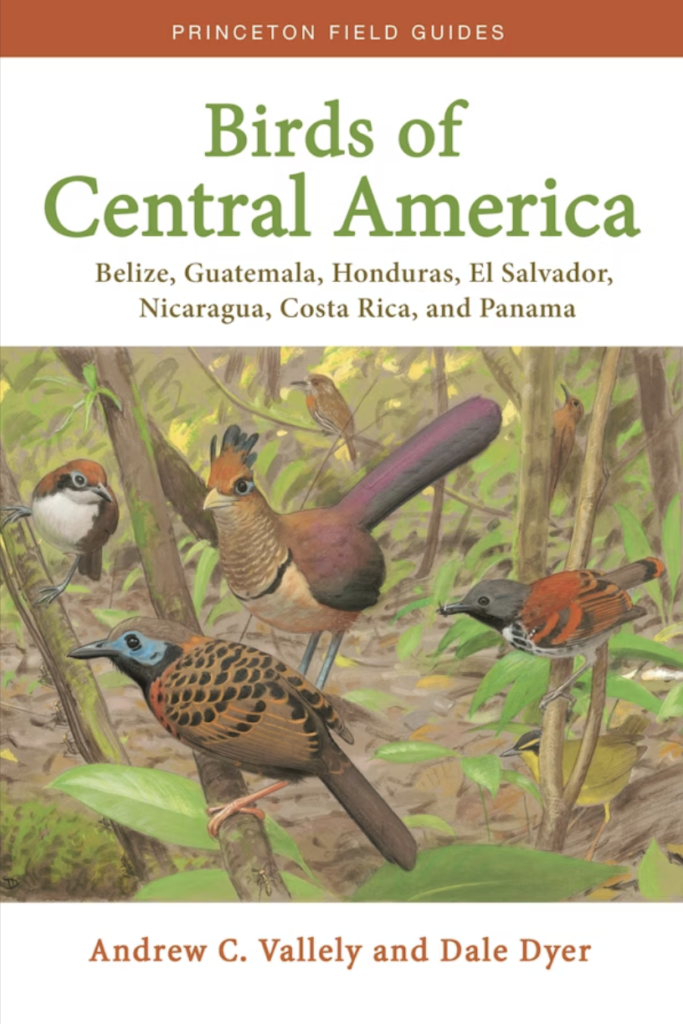

A couple of years ago, I asked my parents for a selection of bird books for Christmas, given that I’d just learned that Princeton University Press was having a sale. Large, detailed bird guides are often quite expensive, but at this time many were being sold for significantly below their usual amounts, and I had my eye on several of them. Fast-forward to December 25th of that year, when I tore the colored wrapping paper off of the boxes with my names on them to reveal the books inside. Two of those books I’ve barely touched—I think one is about waterfowl and the other is about North American rarities. They’ve sat on my bookshelf collecting dust. The other one, however, has gradually replaced the Sibley Guide to Birds as my nighttime reading material. Birds of Central America, by Andrew Vallely and Dale Dyer, is not simply a bird guide. It is an in-depth collection of all of the species in the class Aves that have ever occurred in the seven countries that make up Central America, equipped with some of the prettiest, most detailed drawings of birds I’ve ever seen. The cover, especially, is a work of art, displaying seven species foraging at an ant swarm in the understory of a tropical rainforest.

That book came with me to Costa Rica, and I’ve opened it every single day I’ve been here. The cover is now creased, and there are wrinkles and smudges all along the spine. I can still see the image on the front perfectly well, however. There’s the White-whiskered Puffbird and Plain-brown Woodcreeper in the back. There’s the Kentucky Warbler, hiding behind the skinny plant stem. In the foreground are three of Costa Rica’s most iconic antbirds: Bicolored, Spotted and Ocellated. I’ve seen the puffbird and woodcreeper, and I’ve seen two of the antbirds. I’m still missing Kentucky Warbler and Ocellated Antbird. This blog is not about those species.

Smack-dab in the middle of the cover, surrounded by the other six birds, is a bird that looks like a dinosaur. It stands sporting a scaly, brown breast; a black neck collar; a deep green feathered crest atop its head; and, of course, that dark purple, iridescent tail sticking out behind it. There are some creatures on Earth that seem made up, animals that are so mythical and enigmatic that few people ever are fortunate enough to lay eyes on them. This bird is like Sasquatch, but even cooler. This bird is like a roadrunner of the jungle. Seeing this bird is akin to seeing a Jaguar. The bird is the Rufous-vented Ground-cuckoo.

I learned about ground-cuckoos in 2020, during a cuckoo-themed bracket-style voting event that took place in a Facebook group I’m a part of, and I remember being absolutely shocked by their existence. A few ground-cuckoos live in the Old World, but those that stuck out the most were those in the genus Neomorphus, of which there are five, all living in the Neotropics. Learning that Rufous-vented live in Costa Rica helped me choose that nation as a study abroad location. And upon arriving, my dreams were all but crushed.

Rufous-vented Ground-cuckoos are the most widespread of the five Neomorphus, but even they are unreliable and sporadic at best. For one, in Costa Rica, they only occur on the Caribbean slopes of the big, central volcanoes, places with enough intact forest to support the large ranges they need. For whatever reason, though, they are simply absent from large swaths of the country, including the extensive lowland rainforests in northeastern Costa Rica and the jungles of the Osa Peninsula. In South America, they occur in lowland areas, but here, they do not.

One of the most reliable spots to see the ground-cuckoo in Costa Rica is a place called Pocosol Biological Station, a remote research center nestled deep in the Children’s Eternal Rainforest. When I say “reliable”, however, I mean that the cuckoo is spotted there a couple times a year at best. Regardless, it was high on my bucket list to visit Pocosol, but I quickly realized that the logistics would be too much, especially since I am only really able to use public transportation while here.

So I gave up on the cuckoo. There were easier birds to see that were almost as cool. Besides, even if I made it to Pocosol, there was a very low chance of actually seeing the bird.

And then yesterday, on Monday, April 15th, I logged in to eBird. And I just so happened to look at the eBird page for Alajuela, the province I live in here. The top photo was of a Rufous-vented Ground-cuckoo—and the photo had been taken the day before! Not only that, it had been taken at San Luis Canopy, a location only thirty minutes north of my host city, San Ramón. Some quick investigation revealed that not one but SEVERAL Rufous-vented Ground-cuckoos had been spotted at San Luis a few weeks ago, and that they had been fairly reliable since then. Without a second to lose, I went downstairs and asked my host brother if he could call me a taxi. Thirty minutes later, I was on the road north, and just before 11 o’clock I arrived at San Luis.

San Luis Canopy is known less for its birds and more for its adventure activities, which include hanging bridges, a zipline course and bungee jumping, and I hoped, when I walked up, that I wouldn’t need a reservation to get in. The woman at the front desk smiled at me and asked me for twenty dollars, the entrance fee, then told me to wait by the bird feeders for her partner to arrive. I rounded the corner to see a log suspended from a roof by chains, currently covered in Silver-throated Tanagers absolutely devouring bananas.

As I watched the tanagers and a curious coati watching the feeding frenzy hungrily from below, I sat down. I felt nervous. This whole morning excursion wasn’t particularly cheap. Plus, I might not even see the bird. But then again, I definitely wouldn’t see it if I had stayed in San Ramón.

Soon, a man walked onto the patio and beckoned for me to follow. I got in his truck with a local birder by the name of Jimmy, and he drove us down the road for about ten minutes. He then parked, and motioned for us to walk down the trail. Fifty meters into the rainforest, we spotted a large group of birders, all sitting silently by the side of the trail, watching. Most of the birders were locals, but I saw a few Americans, too. So, I sat down, got my camera ready, and waited.

The ants weren’t particularly hard to see. Ground-cuckoos, like antbirds, follow army ants around and feed on the insects the ants scare up. I could only imagine that being three times the size of an antbird means they have to eat that many more insects, which might explain part of why these ground-cuckoos are so rare.

After fifteen minutes, a couple of birders left—they’d already seen the cuckoo earlier this morning. I frowned. Had I missed my shot at the bird? There weren’t many other species around either. One local pointed out the call of a Golden-browed Chlorophonia as it flew over, but that was about it.

Suddenly, everyone was looking behind me, at the other side of the trail. Several birders had just heard bills clacking, a telltale sign that a ground-cuckoo is nearby. People raised cameras that cost more than I’d spent on my entire study abroad experience, ready to capture the ghosts of the jungle. And then, some people started looking through their binoculars.

I caught motion out of the corner of my eye, and looked through my binoculars. There, the flash of a dirty brown wing. Two large, scaly feet. A long, dark purple tail. The ground-cuckoo was here.

“There’s two!” someone whispered.

The ground-cuckoos were here. And then, more movement, and suddenly, a species I’d only dreamed of seeing appeared on a log, seven feet away from me, posing perfectly. I shot some quick photos. Ten or fifteen seconds passed and the second bird appeared. They both gave us humans a quick look before disappearing into the brambles, clacking their bills all the way.

The whole experience lasted maybe thirty seconds, and then they were gone. I’d gotten good photos and good looks, but wanted more. I wanted more time with these elusive birds. But sometimes, thirty seconds is all you get. Still in shock, I lowered my camera. And after twenty more minutes of waiting, I wandered out of the forest.

How do you tell someone you’ve seen a ghost? What should it feel like? I still don’t know. I still can’t comprehend that I actually saw this legendary bird species.

For the next hour I wandered around San Luis. I got another lifer, Pale-vented Thrush. I also got great views of a variety of birds visiting the banana feeders, including Silver-throated, Emerald, Blue-gray and Blue-and-gold Tanagers (the latter of which is another rarity that people had been coming to San Luis to see), Clay-colored Thrushes, Black-cheeked Woodpeckers and a Tawny-capped Euphonia. And then I caught a taxi home.

I still don’t know what to think. When I saw the Orange-collared Manakins, I was ecstatic. When I saw the Yellow-eared Toucanets, I was in awe. But with this species—it almost doesn’t feel real. If not for the photos, I might think I had dreamed up the whole experience. I feel fulfilled and at the same time inexplicably empty, craving more time with this mythical bird. And yet, it may be the only time I ever see this species for the rest of my life. The cover of Birds of Central America means so much more to me now—but it may take me a while to figure out exactly how.

In the meantime, I’m still in Costa Rica for three more weeks, so stay tuned to see what I get up to next!

P.S. Are you a student? Do you want to study abroad? If so, apply for the Gilman Scholarship! I’ll extol its virtues more on the next blog.