Since they were published last spring, our Japan birding posts have consistently received the most views on our “blogging backlist”—and by a wide margin. This is surprising given that Japan is not known as one of the world’s top birding hotspots. We suspect that our blogs’ popularity reflects the surging popularity of Japan as a travel destination—and that those travelers happen to include a lot of birders!

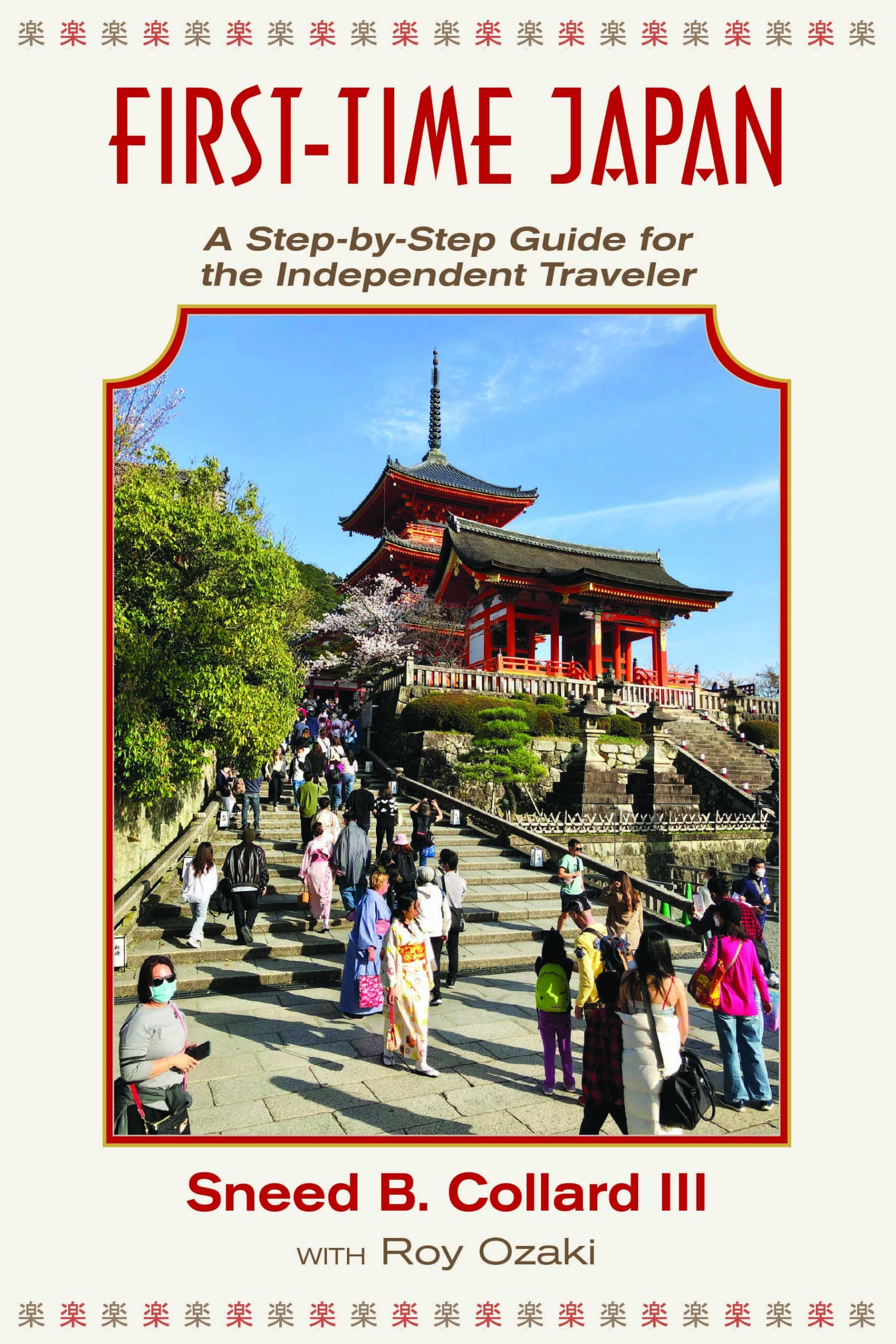

That said, many people find the idea of traveling to Japan intimidating. The language barrier, the complex public transportation system—even Japanese toilets—have led to what I call Fear of Japan among many prospective travelers. However, it was this very intimidation factor that compelled me (Sneed) to write my newest book, First-Time Japan: A Step-by-Step Guide for the Independent Traveler. For birders and non-birders alike, this entertaining volume tells you all you need to know to plan and negotiate your first trip to one of the world’s great travel destinations. Best of all, you can buy it NOW. In fact, why not grab a dozen copies and give them to all of your friends for the holidays? (“Gee, Sneed, that’s an AWESOME idea!”)

As proud as we are of the book, I confess that it is not aimed specifically at birders, so for today’s blog I decided to provide additional advice specifically for you. So without further ado, here are some bonus birding tips for your upcoming Japan adventure.

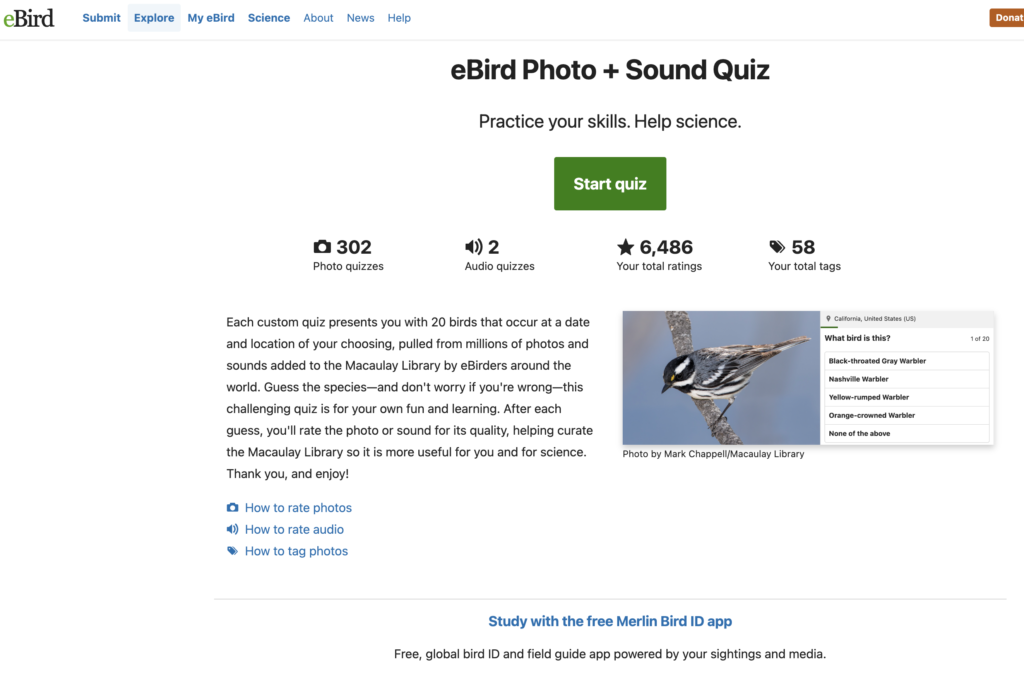

Tip 1: Take Full Advantage of eBird.

eBird is an incredibly valuable tool for any trip, including Japan. If you do not have an account, sign up now at eBird.org. eBird will help you in at least three dramatic ways:

Trip Planning: If you want to time your trip to coincide with the greatest possible number of bird species, simply look up a location in Japan, and study the bar charts for that place. This will tell you when migratory birds arrive and depart. In general, April and May are great birding months for the Tokyo and Kyoto areas— but you have to balance whether you want to hit sakura, or flowering cherry, trees, too. Our three-week trip lasted from the end of March into early April and we managed to time the sakura perfectly while seeing a good number of birds.

Finding Birding Locations: eBird will also identify birding hotspots wherever you are traveling in Japan. In Tokyo, for instance, eBird alerted me to Hamarikyu Gardens, Kasai Rinkai Park, and Shinkjuku Gyoen National Garden—three of my favorite Japan birding experiences.

Learning Japan’s Birds: I credit eBird quizzes with almost single-handedly preparing me to ID birds on my Japan trip. If you haven’t taken an eBird quiz, simply hit the Explore button and scroll down to the “Photo + Sound Quiz” button. These quizzes not only allow you to specify a location, but the time of year, too, so once you have your itinerary laid out you can just keep drilling yourself until you feel confident. In fact, I took so many quizzes that I was able to ID 95% of the birds I saw almost immediately!

Tip 2: Jump on Your Jet Lag.

When you arrive in Japan, chances are you’re going to wake up crazy early (as in the middle of the night)—so whenever possible, put that time to good use. On at least half of my days in Japan, I was out the door at the crack of dawn birding whatever location I happened to be in. Sure, you’ll be tired—but no more tired than if you lay in your bed for six hours hoping to fall back to sleep! Getting out early will also help your internal clock adjust to Japan time.

Tip 3: Don’t Confine Yourself to Birding Hotspots.

Although eBird does show a fair number of birding hotspots, it misses a lot of great locations—probably because there aren’t yet enough birders in Japan to cover them all. The solution? Study a map of where you are and look for any river or other green space and check it out. This paid off for me big time, especially during our quick stop in Nagano, where I nabbed my Lifer Bull-headed Shrike and many other cool birds along the Susobana River.

Tip 4: Make Sure You Have the Best Walking Shoes for Your Feet.

Okay, this sounds obvious, but you will be walking a LOT in Japan. My daughter and I covered six to ten miles a day, every day. Before the trip I bought three different pairs of new shoes/boots and field tested them. The ones that worked best? The cheapest pair of Skechers! You won’t be sorry you put in the extra effort to make sure your shoes are comfortable and sturdy.

Tip 5: Get a Handle on Japan Transportation.

Using public transportation is one of the real joys of visiting Japan—but fills first-timers with trepidation. My book First-Time Japan can help you feel a lot more comfortable with this. Unfortunately, the Japan Rail Pass has gotten a lot more expensive lately, but moving around cities is both convenient and inexpensive. I especially recommend buying the 24-, 48-, or 72-hour “Welcome! Tokyo!” subway pass when in Tokyo and using IC cards (rechargeable credit cards) for almost all other local transportation. Taxis are also very reasonable in Japan, so if a subway or other train won’t get you there, a taxi probably can.

Tip 6: Reread our Previous Japan Birding Blogs.

Kyoto, for instance. Need we say more?

The bottom line: Japan is not Colombia or Australia, but you will still see great birds there. While doing so, you will enjoy one of the most pleasant, fascinating countries imaginable. Just be sure to share your experiences with us when you get back!