Braden and Nick are close to the finish line! This penultimate day of their epic Florida adventure would bring revelation, frustration, traffic jams, and finally, the realization of a key (no pun intended) target species of the trip. They also happened to be nearing their goal of 200 species for their expedition—as well as moving Braden significantly along in his quest to see 400 species during his 2022 Big Year. Read on to find out what happens . . .

Unfortunately, sleep was not in our immediate future after leaving the Keys that night. We pulled back into the Everglades, passing the campsite I’d enjoyed the night before, Chuck-will’s-widow calls sailing through our rolled-down windows. As we drove south in the dark towards Flamingo, the “town” at the bottom of the glades, we scanned the roads looking for our targets: snakes. Soon enough, Nick spotted one, and we pulled off the road, turning on our emergency lights so oncoming cars wouldn’t run us, or the snake, over as we walked down the road towards it. We left Dixie in the car, given that this snake was a Florida Cottonmouth, and probably could have killed Dixie if she got too close. The snake coiled on the warm road, its mouth open, and we showed another group of people that pulled over to see what we were photographing. Our spirits high, we headed back to the car—only to discover that Dixie had peed all over both seats. The smell infiltrated our noses, and we wiped up the mess with various towels and toilet paper that would be going in the next garbage can we came across.

Half an hour later, we rolled into the dark parking lot of a wooded trail near Flamingo. We set off in the dark, using a stick to brush spiderwebs out of the way and looking back frequently to make sure we wouldn’t get lost. Eventually, the trees gave way to a massive field of saltbush, slightly silver in the moonlight. This was the winter home of another incredibly elusive species, the Black Rail. This bird, a member of a group of birds already known to be difficult to find, was the size of a mouse and completely nocturnal. If Mangrove Cuckoo wasn’t the hardest regularly-occurring species to see in North America, it was definitely Black Rail. While hearing them was slightly easier, they didn’t seem to know that as we played for them in the dark, and we walked back to the car, our legs covered in scratches from the saltbushes, after forty fruitless minutes of searching. Nick fell asleep immediately as I took the wheel, just trying to get a little further north before crashing so the driving would not be as terrible during the next few days. I didn’t get far, however, and pulled into another parking lot. Between the smell of urine and the oppressive humidity, I didn’t get very much sleep that night.

At seven, Nick drove us to our next spot, a place called the L31W Canal, a little northeast of the Everglades. Struggling against my fatigue, I stepped out of the car in the brightening sky, and we began trudging along a straight road bordered by brambles on one side and grassy pine forest on the other. We had several goals here, the primary one being a Smooth-billed Ani that had been hanging out for a while. After doing some digging on eBird, I discovered that the ani was a ways down the dusty road, and I sighed, preparing for a long, hot, uneventful hike. Fortunately, I was quickly proven wrong.

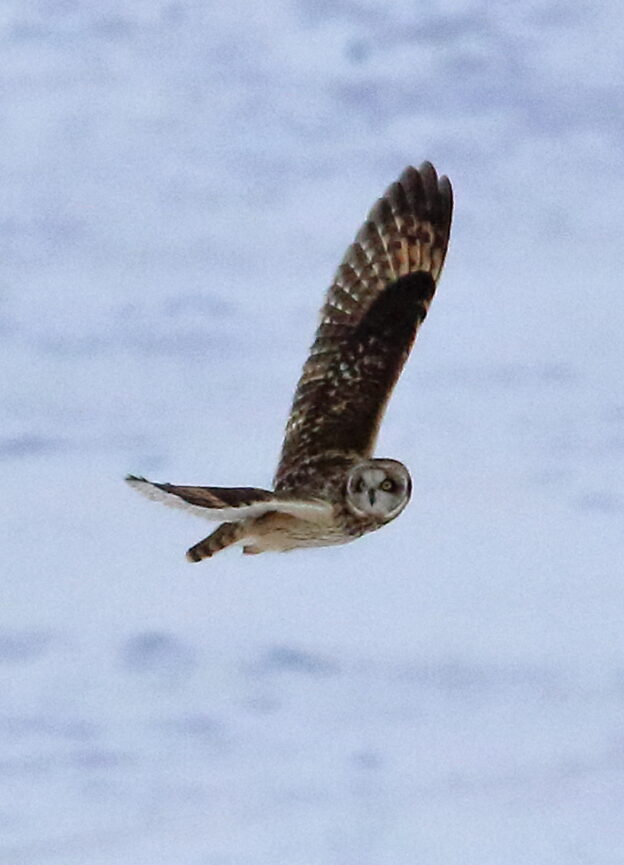

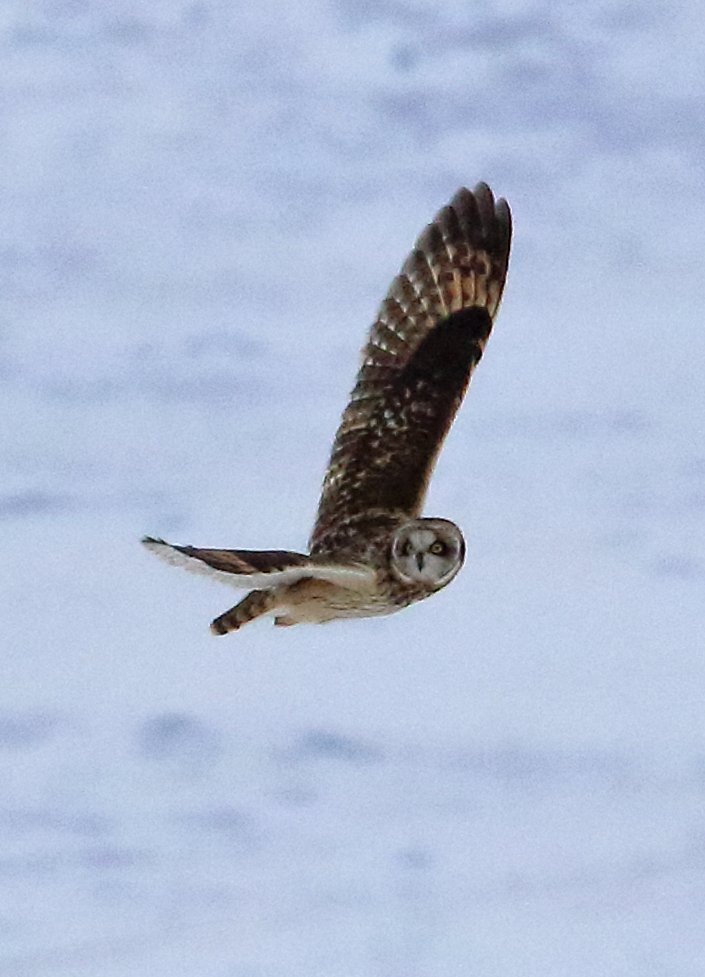

We passed another pair of birders, one of them guiding the other. Nick pointed out the calls of Northern Bobwhites, quail I hadn’t seen since South Texas and had never before heard, and all of a sudden, an orange blur caught my eye. I looked to the right, where a beautiful Barn Owl had just alighted on top of a tall, branchless snag.

“Holy cow, look!” I said, pointing as all four of us birders turned towards it and raised our various devices (camera, binoculars, and in the guide’s case, a scope). The bird had dark eyes and a grayish, circular face peering at us in the morning fog. It took off before I was able to secure any good pictures, its flight reminiscent of a bounding rabbit. We watched the Barn Owl, a species I had only seen the butt of before, our eyes transfixed on the vibrant orange of its wings as it floated around for a while and then disappeared. It was almost like the birds had seen my poor mood and responded accordingly, putting the smile back on my face—and they were just getting started. In fact, the best birding of the entire trip unfolded before us.

As we scanned the pine savannah to our right, searching for White-tailed Kites, Nick pointed out Eastern Meadowlarks, a bird I somehow hadn’t seen until now. Pishing in agricultural parts of the walk yielded a variety of sparrows, including Savannah and, surprisingly, a Grasshopper Sparrow, a bird I associated with the shortgrass prairie of Eastern Montana rather than the humid scrubland of south Florida. More Swallow-tailed Kites appeared above us, circling above the pineywoods as if cheering us on. At one point, a bright red bird zoomed across my path, briefly perching up in a low bush—a male Painted Bunting! The bird was even more stunning than I’d expected, with its deep blue head, green back and brilliant crimson belly lit up in the sun.

While we didn’t find the ani, the other birders pointed out other rare species to us. This place seemed to be a rarity hotspot, which became apparent with a kingbird flock we found. Western Kingbirds were regular winter residents in this area, but this flock also included both a Cassin’s Kingbird (a Western species) and a Tropical Kingbird (a tropical species), and I learned the difference between the three as we watched them fly around us. As much as Nick and I wanted to stay longer, we had miles to cover and Mangrove Cuckoos to find, so we said goodbye to the other birders and began the drive through the glades towards the Gulf Coast.

Yet again, we drove through prime Snail Kite habitat, and yet again, we found no Snail Kites. The sawgrass marshes gave way to densely forested glades as we drove along the Tamiami Trail, and we pulled into the visitor center for Big Cypress National Preserve for a quick glance around the center grounds. While we did see a fair number of birds along the drive and at the visitor center, the main attractions were the aquatic creatures. Amazingly, we spotted a pair of porpoises in the canal as well as a Brown Pelican, both an unusually far distance inland. That meant that somehow, this canal must have had some saltwater. What’s more, at the visitor center we found large schools of fish, including mean-looking Florida Gar. In front of our eyes, a Softshell Turtle snagged one of them and was promptly ambushed by several more. However, the most mind-blowing animals were the alligators. Dozens sulked in the canal, and at the visitor center alone I counted thirty or so, all within several feet of the humans peering at them from the safety of the boardwalk.

Eventually, the scenery changed as we left Snail Kite habitat and entered the habitat of the snowbirds, people who migrated south from the northern United States to their homes in the warmth of Florida. More specifically, we were in Cape Coral, a hot, concrete-covered town known for its tourists as well as another species that I’d only seen previously in the prairies of Montana: the Burrowing Owl. A threatened, urban owl population existed in this part of Florida, surviving in parks, yards and abandoned lots here only because of the protection the city provided. As we pulled up to the Cape Coral Public Library, we saw the fencing and stakes marking their burrows, although no birds were to be found. The heat of the day seemed to be keeping them down, so we headed west, towards our last chance at Mangrove Cuckoo: Ding Darling National Wildlife Refuge on Sanibel Island.

Again, this refuge caught me off guard. I’d expected large marshes and ponds, similar to Montana’s refuges. Instead, we were met with thick, tall, healthy mangroves. The trees were larger and denser than what we’d seen in the Keys, and more accessible too. We drove the main refuge loop, stopping at various trails to play for the cuckoo. One boardwalk in particular displayed the complexity of the Red Mangrove ecosystem, giving us great looks at the trees’ prop roots as they plunged into the shallow, salt-covered mud, and the crabs scampering up their trunks. Fish leapt from the water of the mangrove-encased bays, and we spotted a few shorebirds and waders wherever land showed itself. Here, again, the primary songs we heard were those of Prairie Warblers, singing from all around us in this perfect breeding habitat. And yet again, more Swallow-tailed Kites flew over us, reminding us of the excitement we’d felt when we’d first seen them at Merritt Island.

As we left Ding Darling, cuckoo-less, we discovered what else the area was known for: traffic—the worst traffic I’d ever been in, hood-to-bumper cars stretching for miles as people tried to get off the island. We probably could have gotten off Sanibel faster if we’d been as we covered three or so miles in roughly an hour. Eventually, though, we made our escape, and headed to a nearby baseball field in a last ditch attempt for Burrowing Owls. Again, though, after half an hour of walking around, they evaded us, frustration rising inside us. While the day had been great, we’d missed every single target—no ani, no cuckoo, no kites and no Burrowing Owls, not to mention the uncomfortable night spent looking for nonexistent Black Rails. As the sun began to set, a baseball game started next to us. I stared as the young Little League players hit line drives over each others’ heads. A single ball flew into the outfield, and then I saw it: yellow fencing, located just beyond the baseball diamond. I raised my binoculars, revealing two brown lumps perched on the chain link fence within the yellow caution tape.

“I’ve got em!” I said, and Nick and I began running, Dixie leading the way. As we got close, we put Dixie on a leash, lying down to photograph what we’d found: two incredibly cooperative Burrowing Owls perched in front of us, one on the lawn and one on the fence above the first. They stared at us, their mottled brown-and-white pattern complementing their intense, unmoving eyes. Nick and I moved a little further to take a selfie. Finally, we’d found something we were looking for!

We ended our day at a campsite just south of Gainesville at roughly eleven o’clock, a surprisingly earlier bedtime compared to the rest of the trip. While my goal was sleep, Nick went off in search of Eastern Whip-poor-wills. I lay there, in the back of Nick’s truck, thinking about where we’d been. After spending the day in the glades and the mangroves, we were back in the Pineywoods, hoping for another chance at their birds tomorrow before heading back to New Orleans. While we’d gotten several of my target birds for the trip so far, we’d missed an unfortunate number, and I’d hoped that tomorrow would go better. Would it? Or would we miss everything yet again, to return to Louisiana only with a few of the birds we’d set out to find? Stay tuned to find out!