You may have noticed more references to gulls in our recent posts (see, for instance, “Birding Race Point” and “In Search of the Marbled Murrelet”). Or maybe not. Either way, Braden’s and my interest in gulls has been on the rise in recent years, and for good reason. Gulls are fascinating, beautiful, adaptable creatures worthy of attention. “So why didn’t you pay more attention to them before?” Roger, Scott, and some of our other loyal (and snarky) readers may ask. The reason is simple: gulls are hard. Many of the adults look similar, but if that isn’t perplexing enough, most gull species go through multiple molts which make them look radically different seasonally and from year to year—and frustratingly similar to other gulls in their various molts. The bottom line: to even approach competence identifying gulls, you have to devote a LOT of time to it, and finally, after about a decade of birding, Braden and I have felt ready to dip our toes into this task. Imagine our delight, then, to discover the release of a brand new book from Amar Ayyash, The Gull Guide: North America (Princeton University Press, 2024).

As soon as I heard about The Gull Guide, Amy and I bought a copy for Braden for Christmas. I quickly realized, however, that I wanted a copy of my own, so I contacted Princeton University Press and asked if they would like me to review the book. A week later, my own fresh copy arrived. Flipping through it, I recognized that I may have taken on more than I bargained for. The Gull Guide, I saw, is no mere specialized guide to a group of birds. It is a magnum opus—or in this case, a magnum gullpus—by one of the world’s foremost authorities on a subject. But let’s get to it . . .

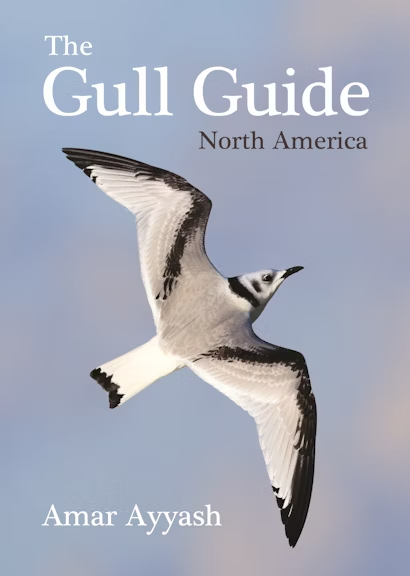

First Impressions: attractive design; gorgeous photographic illustrations; logically and intuitively organized; comfortable to hold in your hands (really!).

My first casual flip through The Gull Guide conjured up a deep feeling that I was holding the Rosetta Stone to an important part of the birding universe. Upon the author’s suggestion, I started by reading the introduction and, I gotta say, this alone made the book worth buying. To wit, even though I knew that gulls seem to thrive in human-created places such as garbage dumps and parking lots, I had no idea just how successful and adaptable they are. To quote the author, “No gull species is known to have gone extinct for as long as modern taxonomy has kept records (Dee 2018). In many ways, they are similar to Homo sapiens: omnivores exploiting and consuming whatever they cross paths with.”

About fifty species of gulls inhabit the planet (fewer than I would have guessed), and The Gull Guide provides coverage of thirty-two that have a presence in North America. The author divides these into three categories:

Small Tern-like and Hooded Gulls

Gulls in the genus Larus

The Herring Gull complex (which is also made up of Larus species, but stands out for the difficulty in identifying and classifying them)

If I had any hope that The Gull Guide would help me learn to easily identify all of these different species, the author quickly laid that fantasy to rest. “It is important to accept that identifying every gull 100 percent of the time is an impractical undertaking,” he states early in the book. “The sooner we come to terms with this, the sooner we’re able to enjoy gulls for what they are. Struggling with an identification should be looked at as an opportunity to grow and cultivate our craft.”

Yeah, sure. Easy for him to say! For my part, I was eager to start building my skills. I therefore proceeded to read the excellent chapters on gull body parts, molts, and overall identification features. Then, I swooped into chapters on individual species.

As you would expect, for each species the author provides a basic overview followed by detailed information on the bird’s range, identification, molts, and hybrids—an especially important discussion since gulls are famous for hybridizing with each other in ways that are often difficult, if not impossible, to figure out. Part of what makes the book so impressive, though, is the inclusion of up to dozens of color plates for each species. These show each bird in different molts as well as geographic variation within the species, and abundant examples of hybridization as well.

Although The Gull Guide is very useful for beginning birders, it is clearly written and designed to accommodate expert birders, including those who wish to make the study of gulls one of their primary birding pursuits. As someone in between those two extremes, I have been using the book to tease out some of the gull challenges I have myself encountered—distinguishing between hybrid Glaucous-winged Gulls and Herring Gulls, for instance, or Franklin’s versus Laughing Gulls.

I especially pored through the gulls we have here in Montana, beginning with our most common species, the Ring-billed Gull. Here, I noticed something that could use correction, or at least more explanation. Ring-billed Gulls can be readily found in many parts of Montana throughout the year, and yet the range map for the species shows them as “year-round” only in certain Great Lakes locations. Braden confirms they are also on the eastern seaboard throughout the year, and eBird bar charts also show them as present throughout the year in many other states. I’m sure the author knows this, so in the next edition, to avoid confusion, I’d like to see his reasoning or methodology for how the range map is created.

That aside, I am sure that The Gull Guide will become a dog-eared companion for both Braden and me as our expertise and interest in this fascinating group of birds continues to grow. This isn’t the first reference book a beginning birder will want to buy, but I highly recommend it for anyone expanding birdwatching beyond their backyard feeders, or for those intrigued by gulls and their fascinating biology.

Overall Rating (on a scale of cool birds): Ross’s Gull (highest)

You can order The Gull Guide from your local independent bookstore, Buteo Books, or directly from Princeton University Press. Please tell them we sent you!