This week we are delighted to present our first guest post from Scott Callow. Scott and I (Sneed) met in the fourth grade, endured Boy Scouts together, and have spent hundreds of hours in the outdoors together. Scott majored in environmental studies and is one of the first people ever to take me birding, at Coal Oil Point in Santa Barbara. We have refreshed our friendship many times, including with several memorable recent birding adventures (see our posts “Chasing Migrants, Part I: Swifts, Peeps, and Plovers” and “Abbotts Lagoon, Point Reyes National Seashore”). We are also fortunate to have photos by Scott and his buddy Steve Rosso (the bird photos) to share. If you are enjoying FatherSonBirding, why not subscribe by filling out the “Subscribe Now” box down in the right-hand column?

(All photos copyright Steve Rosso or Scott Callow.)

My former work colleague, Steve, and I spent 2 hours deciding which walks and talks we would do at our first winter Morro Bay Bird Festival. It was just over a week since the registration opened. Everything we chose turned out to be full, even with over 263 events, 191 of them field trips. Lesson learned. (We later learned that the Pelagic Boat Trip filled within an hour.) We were able to sign up for two outings, a Big Day at the inland Santa Margarita Lake and a “Back of the Bay” walk in Los Osos. Steve also made the wise demand to stop at the Pinnacles National Monument on our way down, and convinced me to spend the extra money ($55) on a boating tour of Morro Bay itself. (Readers are encouraged to open up a map of the region.)

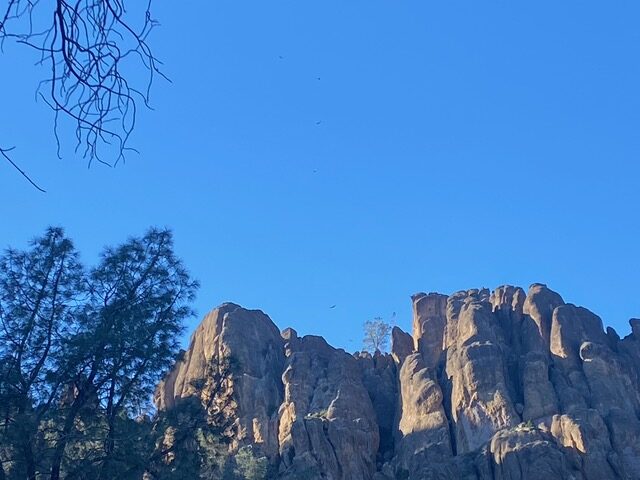

Our first stop was along the lonely Highway 25 between Hollister and Pinnacles’ east entrance. We badly wanted one soaring raptor to be a California Condor but it turned out to be a Golden Eagle. Later (2-3pm), at the observation overlook a mile up the Condor Gulch Trail, more than 15 dark soaring birds suddenly appeared as a group from behind the eroded sandstone Hain’s Peak. I confidently identified four as Condors, one as a Golden Eagle (clearly seeing the difference between each’s white markings on the undersides), and many Turkey Vultures. Steve’s new camera clicked away. At the trailhead, a ranger told us that, years ago, the population was below 10 individuals when reintroduction began and now the local population had swelled to “three digits.”

The next morning we embarked on our first festival field trip: a Big Day at Santa Margarita Lake. It was led by Mark Holmgren, retired curator of the natural history museum and collection at UC Santa Barbara (my alma mater and where Sneed got his master’s degree). Highlights included comparing Eared, Horned, Western, Clark’s and Pied-billed Grebes, listening to Fox’s Sparrows, California Thrashers, and Wrentits, and observing raptor behavior. Speaking of, we saw Ospreys and Bald Eagles fishing (one birder theorized the adult eagles were teaching the juvenile), two Peregrine falcons mobbing a raven, and two Peregrines (perhaps the same) apparently fighting over food in mid-air or in courtship display. I got good looks at the yellow lores of a White-throated Sparrow.

Tired from our long day, we drove to the Morro Bay Community Center downtown and attended one of the two receptions. Included in the cost of registration were free local wines (multiple pours allowed), and extensive noshing trays of cheese, meats, veggies, crackers, and artisan chocolates. The adjacent bazaar impressed with booths for 3-4 high-end binocular/gear manufacturers, book shops, authors, nature art and nature organizations. The bazaar was well attended and the noise generated rivaled that of a Spring morning chorus.

Our dinner at Morro Bay’s affordable, healthy and creative Asian fusion cafe, Chowa Bowl is recommended, as is the lunch combo Big Deal of sushi roll and ramen noodles at Baywood-Los Osos’ funky hangout, Kuma. This is important info to a birder even though food and beverages are barely mentioned in The Avian Survival Kit chapter of Birding for Boomers. Good food and libations can elevate a birding trip. (Editor’s Note: We at FSB take exception to this criticism, as we have frequently mentioned fine dining establishments such as McDonald’s, Wendy’s, and Starbucks.)

Next day’s Back of the Bay trip was not only highlighted by lunch, but by Audubon’s Sweet Springs Nature Preserve. It’s a small preserve with a spring-fed creek and excellent views from its wooden observation decks of the bay’s mudflats and its shorebirds, ducks, gulls, and terns—tons of them (which is saying a lot since birds are so light.) With Morro Rock and Morro Dunes in the background, we saw Lesser and Western Sandpipers, too many Brants to count, 30+ Green-winged Teals, 4 Blue-winged Teals, American Wigeon, Northern Shoveler, Bufflehead, Long-billed Curlew, Killdeer, Black-bellied Plover, Great Egret, and Greater Yellowlegs. We learned the Greater has three notes in its call compared to the two notes of the Lesser. Ring-billed Gulls, Belted Kingfishers, and Forster’s Terns were seen flying above the bay.

In the narrow woodland area between street and bay we saw both Hairy and Nuttall’s Woodpeckers, and Chestnut-backed Chickadee. Then, local guide Dean led our car caravan down the road apiece to his friend’s house which sported about six bird feeders that earned a hot spot ranking on eBird. More chickadees, the ubiquitous House Finch, the most common local warblers—Yellow-rumped, Orange-crowned, Townsend’s—and Lincoln’s, Golden-crowned and White-crowned Sparrows. We also saw our Oak Titmouse, formerly lumped with Plain Titmouse, at the bird feeders. Its range is mostly endemic to California (stretching into parts of Oregon and Mexico) and the bird shares its place with the Acorn Woodpecker as a signature species in California’s oak woodlands.

Dean also shared his mnemonic for our (Pacific Group) White-crowned Sparrow – “Awf man!, I dough-ont wanna see”. It’s a bit of a stretch but “I don’t want to see” sums up many people’s self-engineered denials of science nowadays, so I decided to add it to my mnemonic checklist.

The rarity highlight of the trip was the sole Blue-winged/Cinnamon Teal hybrid. I “put good eyes on it” but Steve left his camera in the car because he logically thought he’d get better shorebird and bay bird shots on the following day’s boating trip.

Our inside-the-bay boat trip the next day also included a fellow (and local) birder, Mike, who led bird trips. Steve and I learned a lot from him. The trip was created as a photography outing and the leader focused on pointing out good shots. The captain, also a birder, put the boat in good lighting and locations for the photographers. We were inspired to overtip him. The trip started in a downtown marina and we made a loop up to Morro Rock, along the rock jetties past the bay’s opening to the ocean, and then back into the bay to the mudflats of the Morro Bay Estuary. As we returned back to the docks, we passed the Morro Bay State Park Boardwalk, the Museum of Natural History, the Morro Bay Water Access, and Heron Rookery Natural Preserve—all excellent spots to bird from the shore, and perfect for photographers from the water due to the sun’s location.

We saw Peregrine Falcons above The Rock, Black Oystercatchers and Black Turnstones on the rocks, Black-crowned Night Herons in the trees, Ospreys on the masts, Common and Red-breasted Mergansers, several Eared Grebes and a Horned for comparison, and a nice collection of Brandt’s, Pelagic, and Double-crested Cormorants floating on a wooden raft. The Brandt’s Cormorants were especially striking with their iridescent coats and bright blue throat pouches. We were surprised to see some of the adults sporting very early breeding plumage marked by brilliant white “whisker” feathers around the ears and shoulders.

Further inside the bay near the mudflats we saw large numbers, reaching into the hundreds, of Double-crested Cormorants, Marbled Godwits, and other shorebirds too far away to ID, plus good showings of White Pelicans, Ospreys, Ring-billed and Western Gulls, Northern Pintails, Buffleheads and Long-billed Curlews, Willets, and Greater Yellowlegs, as well as other common shorebirds not listed. Mike told us that the Pelagic Boat Trip ($160) was fantastic. If interested, check the bird list from the trip on the festival’s website.

The last night’s keynote speaker was Kenn Kaufman, author of Kingbird Highway, multiple nature guides, and his new The Birds that Audubon Missed: Discovery and Desire in the American Wilderness. He extolled birders to persist in their nature explorations, even beyond birds, and to pause the inclination to aggressively list in order to truly observe. He described the Morro Bay region as a “globally important ecological area” and the all-volunteer festival as top-notch and well organized, ranking it among the highest of the many he has attended.

232 species were identified collectively during the 5-day festival in mid-January. Events included typical bird walks, birding by boat, bicycle and kayak, birding for youth, beginners and advanced birders, birding with wine and olive oil tastings. Sites extended beyond the Morro Bay area including the Kern National Wildlife Refuge, the Carrizo Plains Ecological Reserve, various ranches, Atascadero, San Luis Obispo, and Pismo Beach. Check out the Long Report of the Festival Events Including Details on the website. More details than you will need to convince you to make next year’s festival are found at morrobaybirdfestival.org.