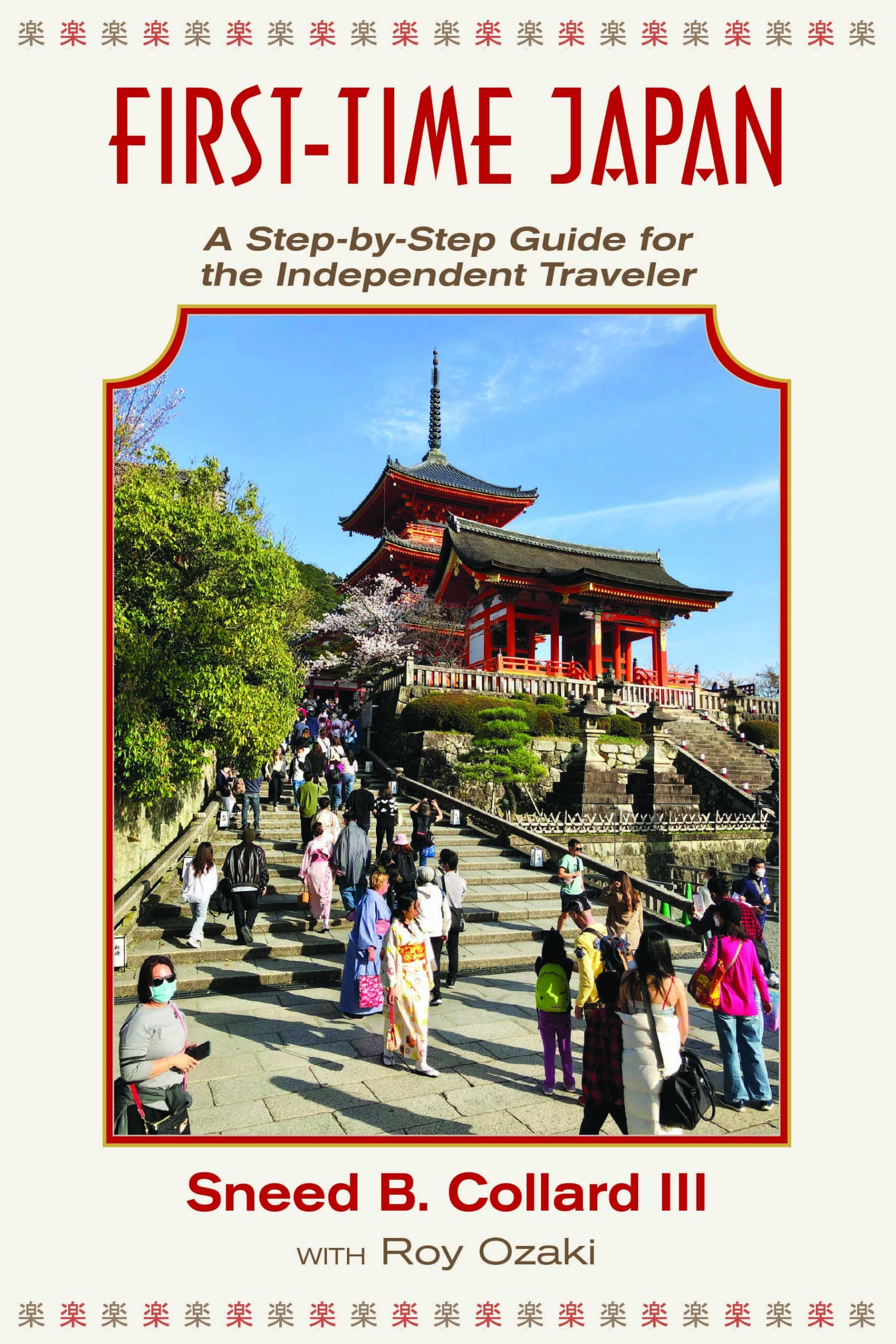

Since we published them, our birding posts about Japan have been read in more than a dozen countries. If you are planning your own trip to Japan, you’re in luck! Sneed’s new book, FIRST-TIME JAPAN: A STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE FOR THE INDEPENDENT TRAVELER, tells you everything you need to know about how to plan your trip to this remarkable, yet sometimes intimidating, country. Order now by clicking here.

Well, I warned you it would be a while before you heard from us again, but we hope you find the reasons acceptable. Braden has been chasing salamanders and frogs in Maine while I have spent the last three weeks with my daughter, Tessa, in Japan! We had dreamed of visiting the Land of the Rising Shopping Mall for many years, and the country and people delivered in every way. While birding was not the purpose of the trip, you might guess that I took advantage of every opportunity to get to know Japan’s avian wildlife—experiences I’d like to share in the next few posts, starting with the focal point of Japanese civilization, Tokyo.

While we planned to visit several Japanese locations, Tessa and I agreed that we wanted to spend the most time in Tokyo. Accordingly, we reserved five days there on the front end of the trip and four days to finish up our journey. Wrapping our heads around such an incredibly large and diverse city proved a challenge, but after much research I booked our first hotel near Tokyo Station. Mind you, this is no ordinary train station. Trains for hundreds of destinations come in and out of the place and the station itself is a vast, entertaining commercial complex featuring hundreds of shops and restaurants, many lined along extensive underground “streets”. The area also happened to make a pretty good headquarters to begin birding.

On our first day there, we worked in a visit to Hamarikyu Gardens in between Tsukiji Outer Market (former home of the famous tuna auctions) and Tokyo Tower. While Tessa enjoyed a park bench in the sun, I quickly snapped up six life birds including Eastern Spot-billed Duck, Common Pochard, Tufted Duck, Oriental Goldfinch, White-cheeked Starling, and Brown-eared Bulbul. I was especially taken with the bulbul—only to find that apparently it is the most commonly observed bird in Japan! Still, I didn’t let that dampen my enthusiasm for these noisy, beautiful birds.

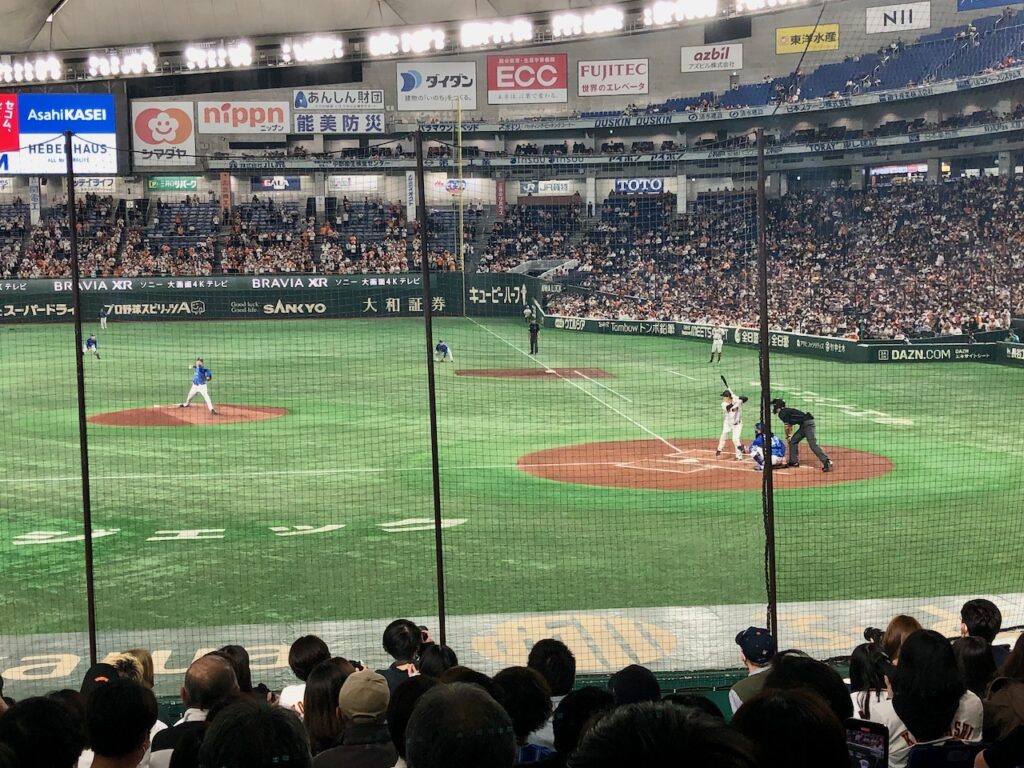

Because of the 15-hour time difference with Montana, I woke at 3 a.m. the next day, and as soon as it got light I let Tessa sleep in and walked over to the Imperial Palace a few blocks away. The grounds were still closed, but I began exploring the moat around the walls and some potentially birdy parks across the street. Right away, I saw a Little Grebe, and then the discoveries grew even more exciting. I saw a small, greenish bird flitting around some bushes—another life bird, Warbling White-eye! Continuing my prowl, I discovered two more lifers—Falcated Duck and Dusky Thrush, two species I had studied intensively before the trip. They put me in a great mood before we went to watch the Yokohama BayStars defeat the Yomiuri Giants 1-0 in the Tokyo Dome that afternoon!

I should pause at this point and say that besides wanting to see Japan’s birds, I had another ulterior motive for birding. When we left Montana, my life list stood at 968 species—perilously close to 1,000. Maybe, just maybe, I thought, I can crack 1,000 while in Japan. In fact, looking over what I might see, I felt fairly confident about meeting that goal—something that spurred me to take advantage of every opportunity.

On the third full day of our adventure, Tessa and I planned to head over to Tokyo Disney to try to score tickets. We did get some and visited the Disney Sea park—but that’s another story. More important, we stopped at perhaps Tokyo’s best birding location, Kasai Rinkai Park. As we got off the train, the reason this park is birdier than others seemed evident: it is one of the few Tokyo locations with remotely natural habitat. Tessa got some of her now-favorite milk tea from a vending machine and settled in to draw on a bench while I hurried off to see what might be living there.

I had not yet met any Japanese birders, but a couple of hundred meters down the trail, a woman with binoculars and a camera saw me looking for birds and silently pointed into reeds next to a pond. “Arigato gozaimasu,” I whispered and crept toward where she was pointing. Sure enough, a half a dozen small brown birds were gleaning seeds and once again, my study paid off. They were Reed Buntings—birds I had hoped, but not expected, to see!

Continuing down the trails I made more discoveries including Japanese Tits and Masked Buntings, both also lifers! Then, walking along the water, I spotted two suspicious shapes about one hundred meters offshore. As I grew closer, the shapes resolved into what has to be one of Earth’s most gorgeous, elegant water birds, Great Crested Grebes!

As I went back to meet Tessa, I was happy with what I had found, but I also knew I had missed some important species here that I would probably not get a second shot at. These included Azure-winged Magpie and any kinds of shorebirds. No matter. I felt grateful for this look at Japanese nature and optimistic for the days to come!