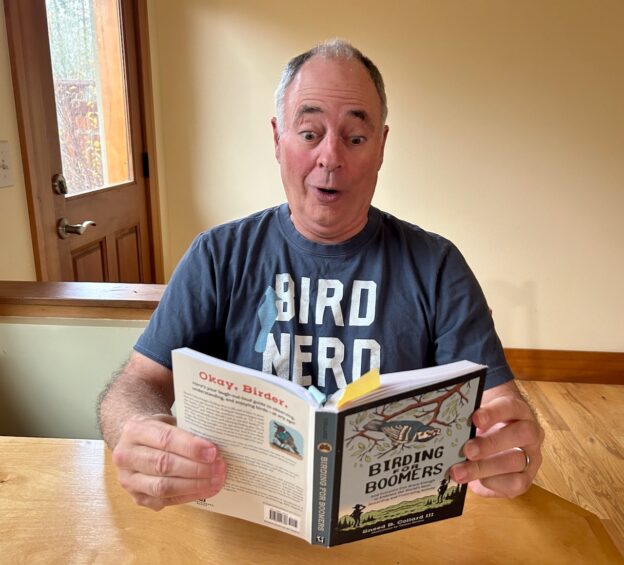

If you’re like me, you never read quite as many books as you’d like. This year, though, I was very fortunate to read and review some outstanding bird-related titles that you’re going to want to consider for your holiday buying. Most—but not all—of these were published in 2025 or late 2024. I’ve also included a few books that aren’t solely about birds—but give great insights into how to protect them. Of course, you will want to begin your shopping with eight or ten copies of my book Birding for Boomers—And Everyone Else Brave Enough to Embrace the World’s Most Rewarding and Frustrating Activity. This popular gift book has received half a dozen awards and even made a couple of bestseller’s lists. Once you’ve placed that order, however, you’ll want to check out the titles below. Please note: we receive no compensation for any of these recommendations (other than a free review copy or two), so the thoughts are all our own. Enjoy!

Purely Enjoyable Bird Storytelling

Let’s start with the “most fun” category of reading—great storytelling that just happens to be about birds. In the past, I’ve recommended such titles as Christopher Skaife’s The Ravenmaster, Joshua Hammer’s The Falcon Thief, and Tim Gallagher’s classic, Imperial Dreams. My favorite title from this year’s reading is Tim Birkhead’s The Great Auk: Its Extraordinary Life, Hideous Death and Mysterious Afterlife. This wonderful, often whimsical tale focuses on an extinct species most of us have heard of, but know little about. Birkhead gets totally into Bird Nerd mode by both explaining the biology and history of the Great Auk, and tracing some of the antics of egg collectors who were totally obsessed with obtaining Great Auk eggs. You’ll love this! See our full review here.

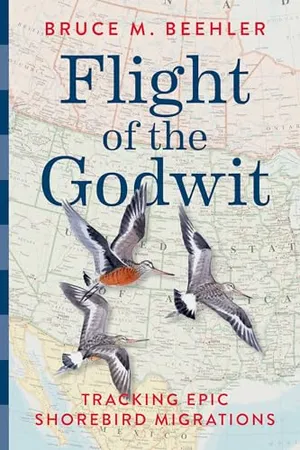

Also on the short list for this category is Bruce M. Beehler’s Flight of the Godwit, a must-read for anyone interested in the remarkable lives of shorebirds—and who isn’t? Through the tales of his own peregrinations, Beehler follows the migrations of many of North America’s most charismatic shorebirds, telling us all kinds of cool things that I certainly never knew before. See our full review here.

Birding Memoirs

My top pick for this category is Christian Cooper’s 2023 book, Better Living Through Birding: Notes from a Black Man in the Natural World. I admit that I put off reading this book for a couple of years after it came out. It’s sheer popularity made me insanely jealous as an author, but once I picked it up, I was captivated. Cooper’s down-to-earth honesty about his life and passion for birds sucked me right in, both with its engaging storytelling and how it broadened my perspective on birding in our culture.

My second pick for this category is Richard L. Hutto’s new book, A Beautifully Burned Forest: Learning to Celebrate Severe Forest Fire. This book is half memoir and half science book and I enjoyed both parts equally. Perhaps as a fellow Southern Californian, I especially related to Hutto’s boyhood experiences exploring the chaparral ecosystem, but I also appreciated Hutto’s impassioned plea to bring common sense to fire management, especially when it comes to protecting burned forests from the ravages of so-called “salvage” logging. See our full review here.

Oh, and if you’re wanting to learn all about Braden’s and my early years of birding, don’t miss my classic first adult book, Warblers and Woodpeckers: A Father-Son Big Year of Birding!

In-Depth Group Guides

Advanced Bird Nerds will definitely want to add Amar Ayyash’s The Gull Guide: North America to their holiday shopping lists this year. Like most birders, I have been—and remain—incredibly intimidated by gulls. Sure, I recognize the adult plumages of many species, but when you start getting into hybrid gulls and first-, second-, and third-year plumage variations, my brain and confidence begin to melt. The Gull Guide does not solve this problem, but it does accomplish two important things. First, it gives great insight into gulls for the casual birder. Second, it offers myriad minute details for those who are bound and determined to become experts on everything gull. Both of these things are accomplished with an extensive, remarkable collection of photos that serve to educate and guide. See our full review here.

A less technical book that may be more to the taste of the casual birder is The Shorebirds of North America: A Natural History and Photographic Celebration by Pete Dunne and Kevin T. Karlson. This beautiful book strikes a nice balance between detail and readability. A lot, but not all, of the information is fairly general, but the photos are wonderful and if you’re a shorb fan, you will enjoy it. See our full review here.

Three More for the Planet

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention three more titles that made a big impact on me this year. The first is Sea of Grass: The Conquest, Ruin, and Redemption of Nature on the American Prairie by Dave Hage and Josephine Marcotty. I thought I knew all about the tragic history of the destruction of America’s grasslands. I did not. This highly readable book provides astonishing insights into how we lost most of our grasslands—and why that destruction continues today. Grassland birds are our most imperiled group of birds, losing at least forty percent of their collective populations in just the last fifty years. If you care about these animals and want to know what we can do to slow their precipitous demise, please read this one!

Similarly, Jordan Thomas’s When It All Burns: Fighting Fire in a Transformed World, gives us an inside look at the often counterproductive politics and decision-making behind today’s “fire fighting industrial complex.” With riveting storytelling and astonishing revelations, this is a perfect companion to Hutto’s A Beautifully Burned Forest.

And if you’re wrestling with how to keep from being overwhelmed in today’s world, where we are confronted by one environmental threat after another, I highly recommend the late Thich Nhat Hanh’s Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet. I read a few pages of this every morning and I gotta say that it helps keep me sane in our complicated, highly imperiled world. Not only does it raise serious questions about how we all live, it provides approaches and encouragement for how each of us can truly make a difference.

Don’t miss our holiday guides to birding equipment and, in our next post, charitable giving!