As light spread across the sky, I slipped on my flip-flops and ventured out onto the porch of our cabin at Owl’s Watch Ecolodge in the department (county) of Caldas, Colombia. Misty clouds clung to the Andean peaks surrounding us. Far below rose the high-rise apartments and businesses of Manizales, a city of almost half a million. Unidentified bird calls rang across the vegetation surrounding us and a couple of flocks of Eared Doves flew by on a morning commute. Suddenly, I saw a shape that stirred familiarity. It landed in a distant tree, but thanks to my amazing new binoculars, I was able to focus in on it. Even though I knew very little about Colombian birds, the way it clung to the side of the tree made me think, “Woodpecker.” Then, I caught a reddish hue on its nape and back, and my excitement rose. When it turned its head, it revealed a large white face patch that clinched the ID. I couldn’t believe it. In my first moments of serious birding in Colombia, I had found one of the birds I most wanted to see: a Crimson-mantled Woodpecker!

As mentioned in my last post, “Layover Birding in Bogota, Colombia”, I had traveled to South America at the last-minute invitation of my friend and FSB contributor, Roger Kohn. Now, only two weeks later, I felt in awe of the fact that we were actually here, about to launch into our first Colombian day of birding together.

Roger had planned our entire itinerary, which included booking our first four nights here at Owl’s Watch, a comfortable new lodge with two modern cabins perched at the edge of a large, protected watershed that ensured a dependable water supply for the city of Manizales below. The lodge had been built by American expat Dennis Bailey and his Colombian wife, Adriana. Interested in restoring land that had been cleared for agricultural activities, they had purchased a farm, or finca, that was an inholding of the nearby protected area. As they worked to revegetate the land and allow it to heal itself, they decided to build Owl’s Watch for nature lovers—especially birders.

The following day, we would be heading out with a guide, but today Roger had wisely allocated time for us to bird and explore on our own—a day to get familiar with some of the local birds and rest up from our two-day journeys from the States. I’m more of an early riser than Roger, but to my surprise, he soon joined me on the porch, eager to get started.

We decided to begin by climbing the long steep “driveway” that headed up from the lodge to the road above. Almost immediately we saw large turkey-like birds that, from taking eBird quizzes, I recognized as Sickle-winged Guans. Moments later, I glimpsed a furtive shape fly across an opening and dive into a bush—a White-naped Brushfinch.

At the top of the drive, we reached a small parking area bristling with even more activity. In the trees surrounding the area, we quickly identified the orange head of a Blackburnian Warbler, and then got super excited to see a pair of equally small birds with bold, sunburst golden throats and breasts—Golden-fronted Redstarts!

As I chased these around, Roger used Sound ID to get onto a bird I never thought we would see, Azara’s Spinetail. Its call sounded like “bis-QUICK! bis-Quick!” and while we never got great looks at it, we were thrilled to get a glimpse of this handsome, skulky species.

From the parking area, we headed down a pleasant trail that would wind its way back to the to the main lodge building, dubbed “the Social.” Soon, a covered viewing platform came into sight and we paused to check out hummingbirds at the feeders and flowering bushes surrounding the spot. Someday, I’ll write about my ambivalence about hummingbirds, but I gotta say, they were spectacular to watch. What got me most excited was seeing a White-sided Flowerpiercer. I’d seen my very first flowerpiercer only the day before in Bogota, and here I was, looking at a second species the very next day!

We continued hiking down the trail, past the Secret Garden, another great birdwatching spot Dennis had set up. Along the way, I spotted a rather plain brown bird that I quickly recognized as a Swainson’s Thrush. As I indicated in my last post, it’s a special thrill to see a bird from “back home” in its alternative, wintering environment. I also took a photo of a nondescript bird that turned out to be a Mountain Elaenia, a kind of tyrant flycatcher.

Soon, we found ourselves back at the Social. David, the fabulous Owl’s Watch cook, fixed us a scrumptious breakfast and we dined while enjoying yet more hummingbirds—at least nine species—along with more flowerpiercers, Rufous-collared Sparrows, and Great Thrushes.

Along with the hummingbird feeders, Dennis’s crew had set up a fruit feeder off to the side, and there we beheld one of the most spectacular of the area’s birds, Blue-winged Mountain Tanagers.

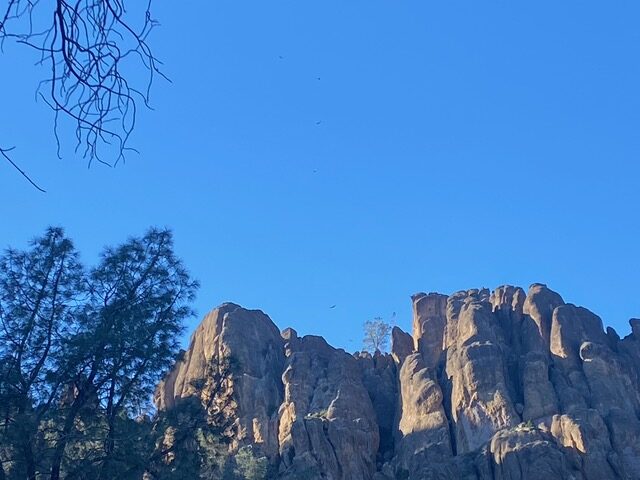

After we got our fill of hummingbirds (if that’s even possible), we took another path that wound around to our cabin. Before our trip, Braden had encouraged me to listen for weird noises, and now I did indeed hear a very bizarre, almost plaintive, series of falling notes. As we rounded a corner, we met the source of these calls—a Masked Trogon! Trogons are some of those birds you always hope to see in the tropics, but when you finally do, you’re left wondering if the bird is really perched there in front of you, or if you’re just imagining it! Fortunately, this was no mirage, and even better, it sat cooperatively while Roger and I did our best to capture decent photos of it against the backlit sky. How did we do? You will have to judge for yourself:

Note: This blog post—and all others on FatherSonBirding—are written by REAL PEOPLE! No compensation or gratuities were provided to us in connection with this post. If you’d like to support FSB, please consider buying one—or ten—of Sneed’s books and contributing to a bird conservation organization of your choice. Thank you!