With fewer birds around, winter is an excellent chance to catch up on bird-related reading, both for enjoyment and education. I find this a perfect time to check out both new bird-related titles, and older books that I have somehow overlooked. Speaking of the latter, during the December holiday my father-in-law handed me Scott Weidensaul’s remarkable 2021 release, A World on the Wing: The Global Odyssey of Migratory Birds (W. W. Norton). I’m so glad that he did!

In A World on the Wing, Weidensaul manages to take an overwhelming body of global information about bird migration and distill it into a series of stories that give the reader a captivating picture of what’s going on out there. The book’s first chapter hooked me immediately with the author’s visit to one of the world’s most vital shorebird stopover sites—and one I knew almost nothing about—the mudflats surrounding the Yellow Sea. These mudflats are nothing less than the linchpin to the East Asian-Australasian Flyway (EAAF), a vast, complicated series of routes used by millions of birds migrating from the Southern Hemisphere to breeding grounds in the far north. According to an online UNESCO article, about ten percent of all migrating birds on the EAAF depend on the Yellow Sea stopover area. They include two of the planet’s rarest shorebirds, the “Spoonie”, or Spoon-billed Sandpiper, with a population estimate of about 500 or fewer, and Nordman’s Greenshank with fewer than 2,000 individuals. Beyond that, the area provides critical support to 400 other bird species, including 45 considered threatened.

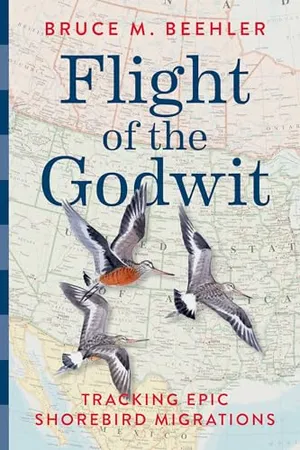

This first chapter sets the tone for a global, diverse journey through myriad aspects of bird migration. One chapter focuses on the incredible physiological adaptations of migrating birds, including their abilities to sleep on the wing, reduce or increase the size of internal organs to optimize weight and function, and navigate by taking advantage of quantum physics. Other chapters focus on species or groups of migrating birds across the globe. Some of these birds, such as the Kirtland’s Warbler and Snowy Owl, will be familiar to many readers while others, such as Bar-tailed Godwits and Amur Falcons, are less so. Every chapter, though, is filled not only with revelations, but personal anecdotes and experiences that make the stories come alive.

Taken as a whole, the book serves as an impassioned plea to protect migratory birds and, well, just do things better on this planet. The crucial mudflats of the Yellow Sea, for instance, are critically imperiled by industrial development, pollution, and interruption of sediment flow caused by thousands of dams across China’s rivers. It’s not that the loss of these mudflats would put a dent in bird populations. It could wipe them out. The author quotes one scientist as saying, “There is no more buffer. There is no more ‘somewhere else’ for these migrants.” The threats to migrating birds are multiple and widespread, varying only in their particulars. In some places, pesticides take terrible tolls. In other places, it’s illegal hunting for local culinary specialties. Almost everywhere, habitat loss and climate change loom large.

Somehow, the author manages to balance these threats with the overarching wonder of bird migration and leaves the reader feeling hopeful—or at least determined—along with being much better informed. This balance, along with the engaging writing style and storytelling make this one of a handful of bird-related books that I consider required reading for anyone interested in birds and conservation.