For my birthday, my wife Amy surprised me with a week-long trip to Vancouver Island, including a three-night stay in Victoria and three more nights at a little cabin overlooking the majestic Pacific Ocean and the Olympic Peninsula across the Salish Sea (or Strait of Juan de Fuca). Amy’s surprising plans delighted me, especially since this was where we honeymooned a couple of decades before, and we’d always wanted to return. I was puzzled, however, when she said, “It’s supposed to be a good place to go birding.” What? Birding? On Vancouver Island? In January? After doing a little research on eBird, however, I concluded that she might just be right. For winter, the area seemed to have a good variety of songbirds, but I got even more excited about the possibility of ocean birds.

Our first morning there, I awoke before dawn, walked to a nearby convenience store to grab nourishment, and then drove our rental car out to McMicking Point just as light seeped across the sky. I was super excited about this spot because someone had reported sixty species there only days before, including several birds that would be lifers pour moi. I had even dragged my large, awkward spotting scope and tripod out from Montana specifically for such opportunities. Alas, I later learned that the “mega lists” I had found on eBird had been compiled by one of the region’s top birders—a guy who apparently could ID a bird miles away just by the way it flew. My experience would prove far different.

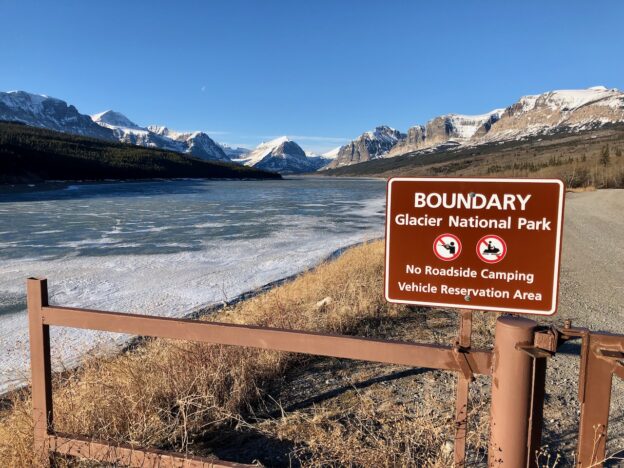

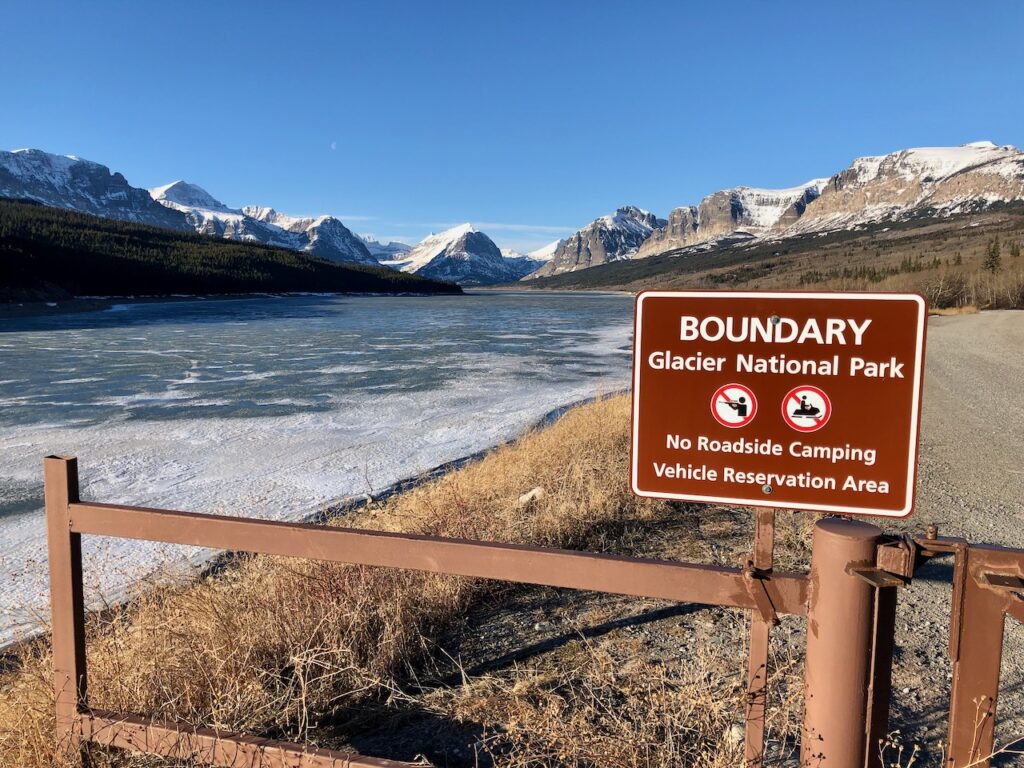

As I set up my scope, my first thought was, “Where are all the birds?” A couple of cormorants—too far away to identify—skimmed the water, along with a few Glaucous-winged Gulls, and I could hear a raven in the neighborhood behind me, but that was it. In such situations, I have learned that it’s important to calm down and be patient—something I am horrible at (just ask Amy), but nonetheless have learned to do. Sure enough, as I trained the scope on some nearby surge channels, I spotted a few Buffleheads and then, to my delight, the trip’s first Harlequin Ducks! In Montana, we have only a narrow window to find HADUs as they breed mainly in a handful of whitewater streams in Glacier and Yellowstone (see our post “In Glacier National Park, When It Rains, It Pours—Animals.”). Because of this, I took extra time to enjoy them.

Through my brand new binoculars (more about these in the next post), I also could see interesting action stirring out on the Trial Islands about a quarter mile offshore. I trained my scope out there and immediately picked up Black Turnstones, Black Oystercatchers, and Dunlins working the rocky shore. Then, I got even more excited as I noted several larger, pale, medium-sized shorebirds. Yay! Black-bellied Plovers! This especially reinforced the value of preparing for any birding trip—especially with birds that are far away. The Dunlins, for instance, would have been more difficult for me to pin down if I had not learned that they were the most likely small shorebirds in the area this time of year. I also had noted Black-bellied Plovers on recent eBird lists for the site, and so was primed to recognize them.

After picking up a few more species, I departed McMicking Point with, I should emphasize, a grand total of sixteen species—not the sixty-plus I had been dreaming about. Still, my next stop, Clover Point, would add a few more good ones for the day. Unlike McMicking Point, where I birded alone, Clover Point was well-trodden by walkers, dog owners and, it turns out, a few other birders. Here, I got closer looks at Dunlins, Harlequin Ducks, and oystercatchers, but also picked up both Red-necked and Horned Grebes and Surf Scoters. A friendly birder named John also joined me and pointed out a group of White-winged Scoters in the distance along with what he said was a Red-throated Loon, which Braden and I had seen recently on Cape Cod (see our post “Birding Race Point: Cape Cod’s Pelagic Playground“). I couldn’t convince myself of that ID, but we did spot a Pigeon Guillemot about a quarter mile distant.

“Is there anything special you’re looking for?” John asked me.

“I’d love to find some murrelets,” I told him with a sigh.

“Oh, we should be able to find you more alcids,” he told me, scanning the water with his binoculars. Alas, our efforts proved to no avail, and I admit that I wrapped up the morning feeling a bit of a failure. In fact, I mentioned to John the list with sixty birds on it, and he said, “Oh, that birder is a local legend. You look at his lists and you think he’s just making it up, but I’ve birded with him, and he’s the real deal. He can recognize almost anything.”

That did make me feel better, but even if I had not learned this, it’s important not to fall into the “failure trap.” After all, you can only see what you can see—and the whole point is to enjoy every bird you are lucky enough to encounter. Also, I reminded myself, my Victoria birding was far from over. I brought Amy back to Clover Point the next day, and while she walked along the cliffs, I enjoyed another nice session, including my only encounter with Surfbirds the entire week. These are some of Braden’s and my favorite rocky shore birds, and it was awesome to watch them foraging along with a larger group of Black Turnstones.

That afternoon, while Amy rested at the hotel, I decided to make the most of the season’s abbreviated daylight hours and take a stroll through Beacon Hill Park, a large park stretching almost from downtown out toward the sea near Clover Point. I intentionally left my camera in the room so I could just appreciate whatever I happened to see—which turned out to be a lot. On the grass right outside of our hotel, I was astonished to see a dozen Yellow-rumped Warblers—birds that I figured ought to be wintering much farther south (Sibley, though, shows them as all-year-round here after all). Once I reached Beacon Park, I began seeing Pine Siskins, Chestnut-backed Chickadees, Red-breasted Nuthatches, and a bird that, because of my crummy ears, always proves a challenge: Golden-crowned Kinglet.

After strolling for about half an hour, I stood watching a Ruby-crowned Kinglet flycatching, something I had never seen one do, when another birder approached. In a wonderfully British accent, he asked, “Do you know that within a quarter-mile of here is a great rarity?” I knew immediately what he was talking about. From looking at eBird lists, I had learned that a vagrant Green-tailed Towhee had showed up in Victoria and had set off a frenzy in the local birding community. John at Clover Point had also mentioned it, but I hadn’t realized I had wandered so close.

“I tried to see it,” my newest birding friend confided, “but you know what I heard—‘Oh, you should have been here five minutes ago.’” Nonetheless, he gave me directions in case I wanted to check it out, and with an hour or so of daylight left, I figured I might as well. I crossed the road and followed a little path up and over a hill until I came to a tall flagpole flying the maple leaf. Sure enough, in the field below, a group of four or five birders had gathered around a small thicket. I quietly approached from behind and spotted movement in a darkened space between two bushes. After a few moments, the familiar shape of the Green-tailed Towhee took the stage.

It was weird seeing a bird that is relatively common in Montana being such a focus of attention here in Canada, but it was cool, too. It helped me appreciate the enthusiasm of birders no matter where you go in this amazing world. What’s funny, though, is that I got much more excited by the Fox Sparrow foraging a few feet away from the towhee. That is always a tough bird for me to find in Montana, so it was great to have one put in an appearance for me here. With that, I made my way back to our hotel so that Amy and I could go find a fun restaurant to dine at. What I didn’t realize is how much good Canadian birding still lay ahead of me.

(For the second part of this story, see “In Search of the Marbled Murrelet”.)