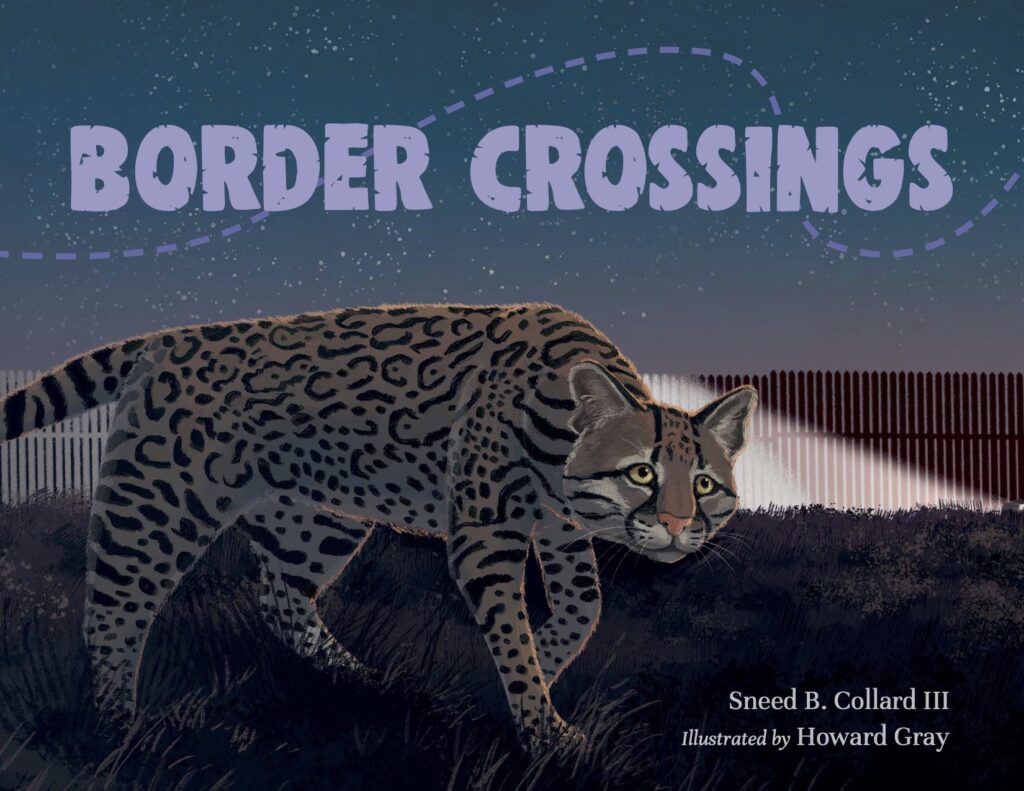

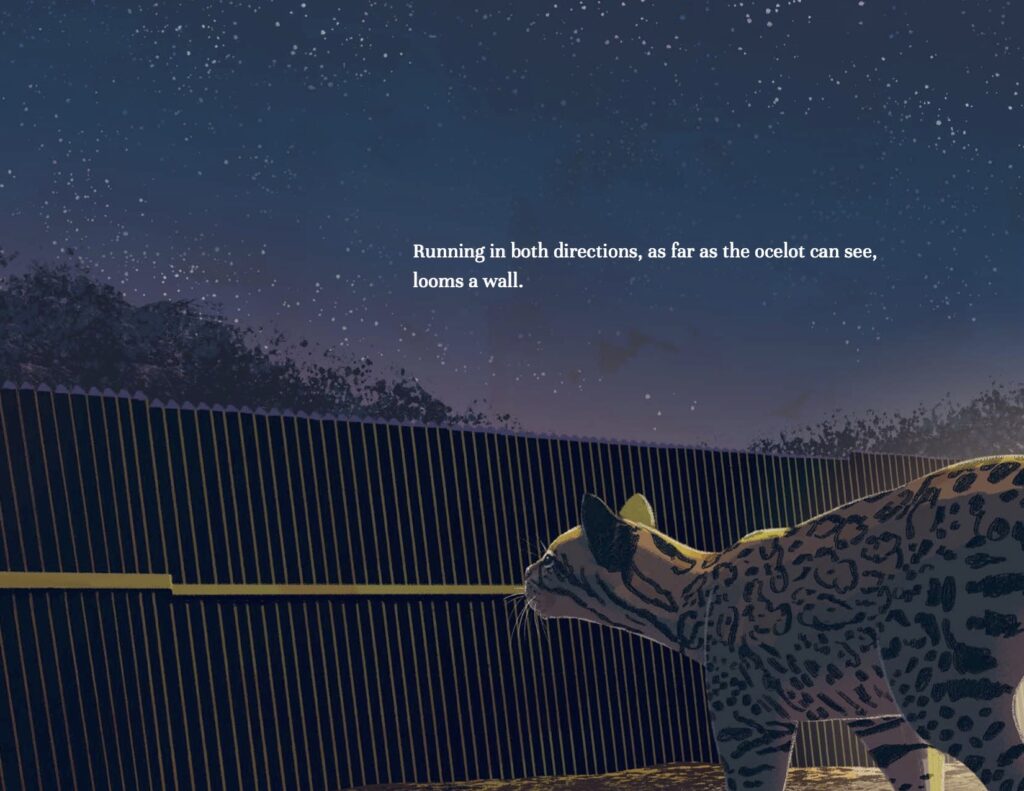

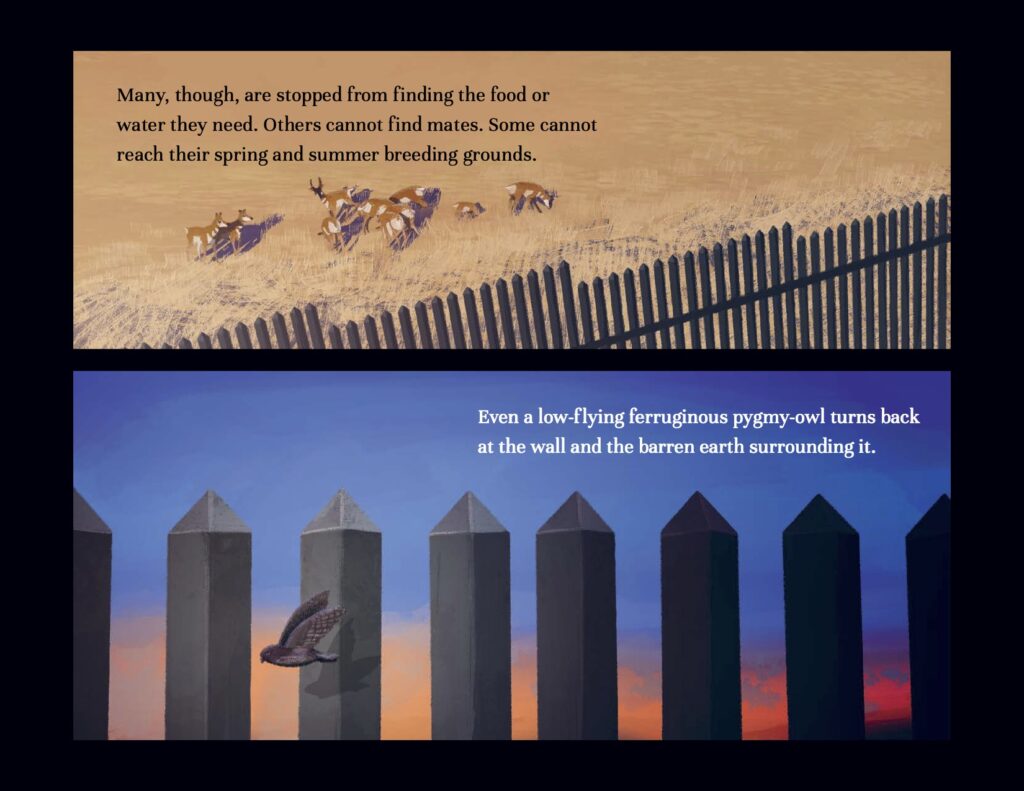

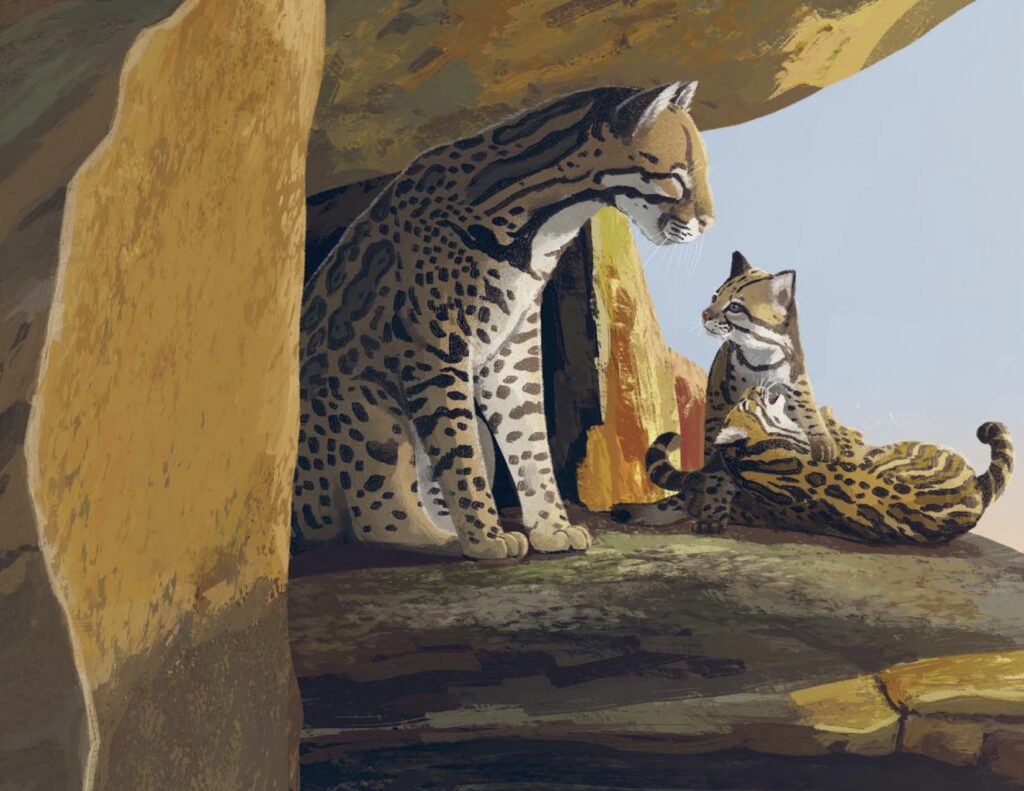

As 2023 winds down, we hope you enjoy our penultimate post on one of everyone’s favorite subjects. Before that, we have some great news to share. Sneed’s picture book Border Crossings has received NCTE’s prestigious Orbis Pictus Award for nonfiction! This is one of the literary world’s top children’s book awards and was inspired by, you guessed it, Braden’s and Sneed’s birding adventures along the US Mexico border. Learn more and order by clicking here!

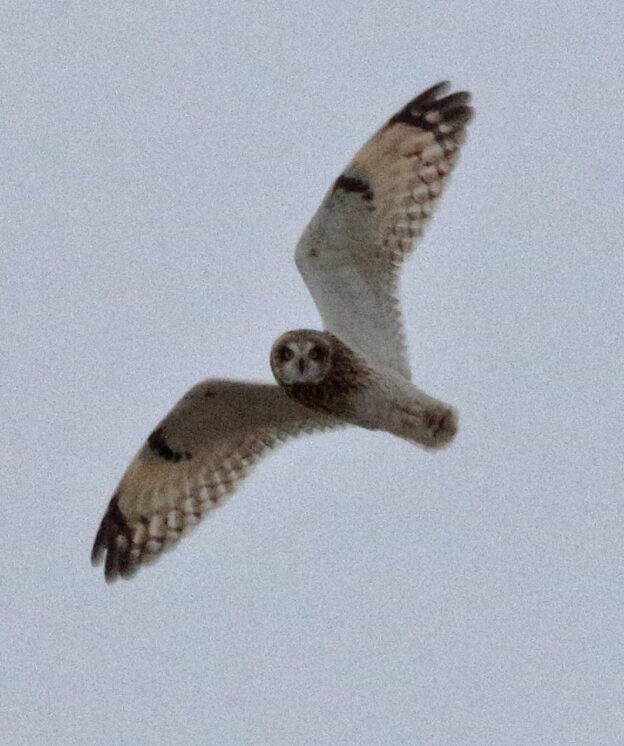

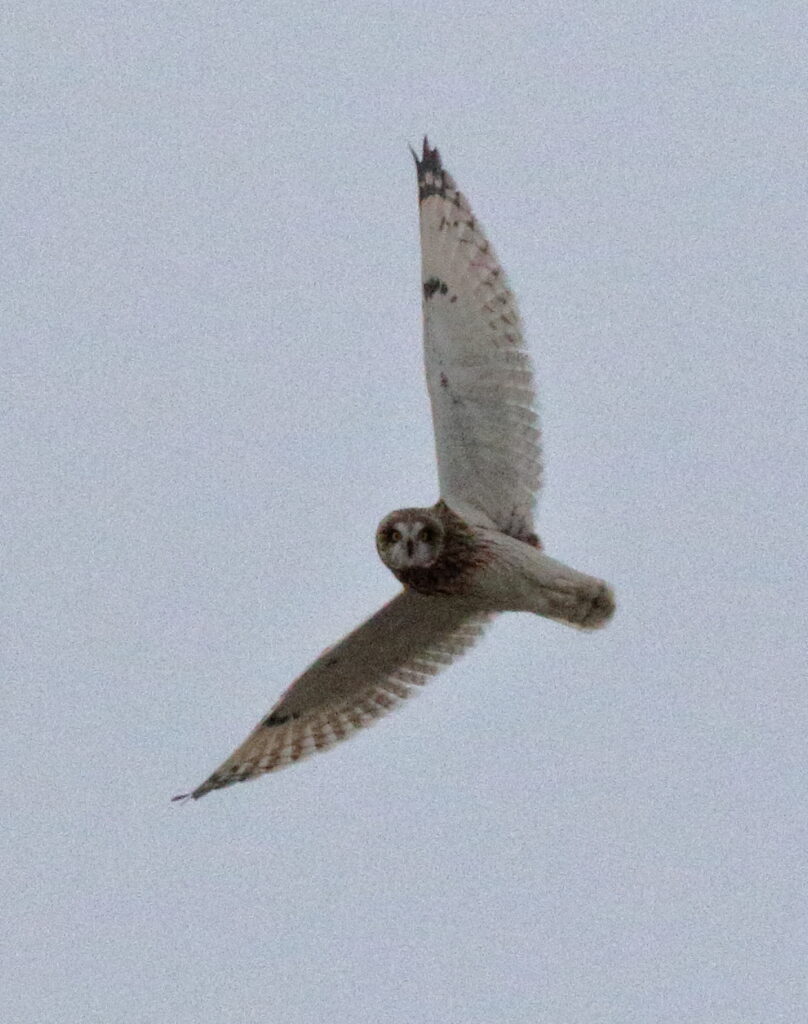

Owls consistently rank among the favorite bird groups of birders, and Braden and I are no exceptions. We’ve had a pretty good year for owls in 2023. It got off to a roaring start with wonderful encounters with Long-eared Owls, Northern Pygmy-Owls, and Saw-whet Owls the first days of the year, and continued with the now-famous Northern Hawk-Owl in Wise River. Unfortunately, after that, our owl experiences stalled. We failed to see both Great Gray Owls and Snowy Owls last winter, nor even a Barred Owl. We also missed both Western and Eastern Screech Owls, though did pick up Burrowing Owls near Great Falls. When Braden got home from college a few days ago, however, we decided we would make one last effort to see perhaps our biggest miss of the year: Short-eared Owl.

We had looked for Short-eareds multiple times in 2023, both at Ninepipe National Wildlife Refuge, and on our forays into eastern Montana. In fact, I had never gone to eastern Montana without seeing one of these spectacular creatures, but this year? Zip. Ditto at Ninepipe, where we can almost always count on at least one SEOW during the year. What was going on? Joni Mitchell’s prophetic lines haunted me:

“I’ve looked at owls from both sides now

From up and down, and still somehow

It’s owl illusions I recall

I guess I don’t know owls at all.”

Why does Joni always have to be so darned depressing? Nonetheless, when our neighbor Tim told me he’d been encountering gobs of Short-eared Owls while out hunting in the Mission Valley, Braden and I were determined to give SEOWs one last try. We parked at Tim’s spot amidst a winter wonderland of frosted fields created by low fog and freezing temperatures that have been blanketing the area for the past couple of weeks. A sign invited pedestrians into the property so unlike our other searches for SEOWs, which relied on driving rural roads for miles and miles, we zipped up our jackets, slung our optics over our shoulders, and followed a frozen dirt path out into a field.

Almost immediately, rodents (voles?) scurried in front of us while Northern Harriers circled the perimeter.

“There have got to be owls here,” I said. “Look at all this prey!”

Well, not so fast. We kept walking, expecting an owl to fly up at any moment, but no dice. We heard Canada Geese, saw magpies and a hawk or two, but no owl. As the road curved left, I decided to crunch my way over to a big group of cattails. As I paused to study it, I suddenly heard Braden shout, and spun around to see a Short-eared Owl quickly flying away!

For those who haven’t seen these creatures, they truly are marvels of engineering. While perched, they appear only medium-sized. Once they take off, they unfurl impossibly long, flexible wings that leave an observer breathless. Like Northern Harriers, which also hunt low over fields and marshes, listening for prey, Short-eared Owls hunt by both sight and sound, moving low and slow, their long wings giving them plenty of lift with minimal flapping. We watched, elated as this one flew in a lazy arc away from us—but it was so much fun to be out alone in the middle of this giant field that we decided to keep walking.

When a fence blocked our way, we turned right and followed an embankment along an irrigation ditch. Braden heard Marsh Wrens, and then we encountered another fence. I pride myself on having good directional sense, so I said, “Let’s head this way back toward the road.”

One advantage to the frozen ground is we could walk across normally wet places without plunging into cold water. We walked in parallel, forty or fifty feet apart, and at one point I saw Braden pause to study another group of cattails. He motioned me over, and I was stunned to see a white face with beady eyes pop out to look at me. A weasel! The mammal was in full winter “plumage,” and it was only the second one we’d ever seen in Montana, so it quickly grabbed “Bird of the Day” honors!

But our owling, it turns out, had just begun. As we headed back toward our car, Short-eared Owls started popping up like jack-in-the-boxes! We tried to spot them on the ground so we could steer around them, but they were so well hidden in the grass and cattails that we never saw one until it took flight. Then we just stood in awe, watching it navigate on their incredible wings until they settled a couple of hundred meters away. One owl even had a little tête-à-tête with a Northern Harrier, exchanging some words neither Braden nor I could make out.

One thing we wondered was why the birds weren’t actively hunting. Prey scurried everywhere, and the cold air shouldn’t have been a problem for such masterful fliers. In fact, Braden and I have seen them active in all seasons and at all times of day, though they do tend to be crepuscular—most active at dawn and dusk—especially in winter. Beyond this, I am guessing that the birds were so stuffed with voles that they could afford to chill out—literally. (But see my earlier comments on my understanding of owls re: Joni Mitchell.)

After observing at least half a dozen of these glorious creatures, we finally made it back to the road. Alarmingly, our minivan had disappeared!

“Geez, where is it?” I asked. “Did someone tow it?”

“I don’t know.”

“Wait a minute,” I said. “This road is paved. Didn’t we park on a dirt road?”

“Oh, yeah,” Braden confirmed.

So much for my infallible sense of direction! As we wandered across fields, we had veered at least 90-degrees off course and ended up in a totally different place than we’d intended. Fortunately, Braden was able to use our eBird track to quickly figure out where our car was actually located. After a short hike down the paved road, and a turn right, we reunited with our faithful birding-mobile.

Seeing one of our favorite birds was a great way to wrap up our Montana birding adventures for the year and made us feel good knowing that great habitat and plenty of food still abounded for this wonderful species. The weasel (probably a Short-tailed Weasel) was also a great bonus. The Short-eared Owl pushed my Montana Year Bird list to 252 species, my second highest total ever. That number would tick over to 253 species an hour later when Braden and I saw a Northern Shrike up near Polson. Braden’s 2023 Montana total reached 198—pretty darned good considering he spent only five or six weeks in the state. None of us can predict the future, but if we all keep getting out there, we can guarantee that 2024 will bring plenty more birding adventures. What are we all waiting for?