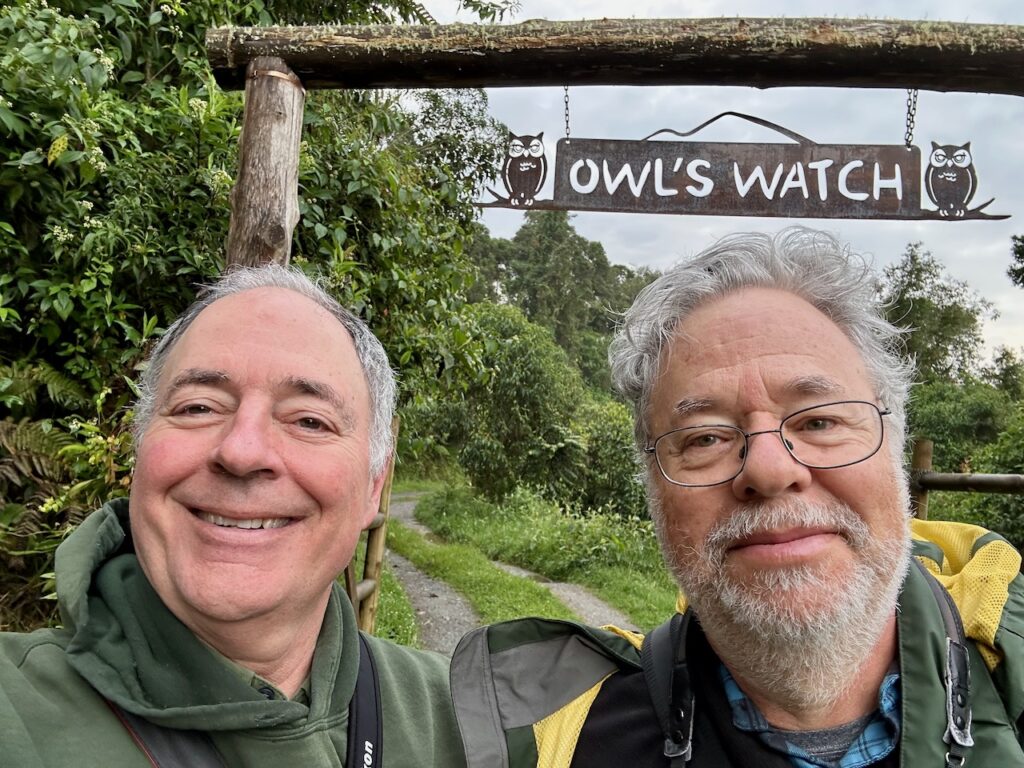

If you read our last post, you know that Braden and I recently completed an epic birding adventure to Costa Rica. One thing I didn’t mention is that, besides offering the chance to see an astonishing variety of neotropical birds, the trip gave me the opportunity to field test an exciting new piece of equipment: the Nocs Provisions Pro Issue 8X42 binoculars. And boy, did I put them to the test!

I must confess that I liked the Pro Issues right out of the box. As I explained in my recent review of the company’s Field Tube monocular, Nocs has put real thought into designing equipment that looks and feels different from the vast majority of products out there. The rubberized protective casing of my Pro Issues features a stylish ribbed design that is easy to grip, yet feels very comfortable to hold. Like the Field Tube monocular, these binoculars also have “pop in” caps for the objective lenses that are much more secure than any other design I’ve encountered.

With my review sample of the Pro Issues, Nocs took the trouble to send me one of their woven tapestry neck straps, and if you purchase any Nocs binoculars, I highly recommend picking up one of these, too. Not only does the strap look way cooler than standard bino neck straps, it is more comfortable against the skin—and easier to attach to the binoculars than any other design I’ve seen. As far as the build, these binoculars couldn’t feel more solid. I fortunately didn’t drop them, but felt that if I had—or if I whacked them against a strangler fig tree—they would survive unscathed.

When I decided to take the Pro Issues to the tropics, I realized that waterproofing would be important—but I didn’t realize how important! For about half of our trip, Braden and I endured one of the wettest “dry seasons” on record. I mean, we got dumped on—to the point where, several times, we just stood under a tree and tried to will the rain to stop. Not only did the Pro Issues take on this full exposure without allowing water to penetrate the casing, the binoculars didn’t fog up even in the worst conditions.

I should mention that one smart thing Nocs has done with their optics is to recess the objective lenses deep inside the tubes. This means that as they hang from your neck, rain won’t land on or “creep around” to the lenses—avoiding a potential constant hassle. One thing I do hope Nocs incorporates into future products is a “faster” focusing knob, requiring fewer revolutions to go from very close to very far focus. This would make it easier to zoom in on fast-moving birds.

Of course none of the above matters without good quality optics, and the Pro Issues definitely hold their own against other equipment in a similar $300 price range. Nocs uses BaK-4 prisms, a higher quality prism that ensures even, full-spectrum light transmission. Like other quality companies, Nocs uses coated, scratch-resistant glass. The result? In bright to medium-low light, I got nice crisp, well-lit, full color looks at birds, even from a good distance. Taking 8X42 instead of 10X42 binoculars proved a good choice for in-close rainforest conditions by giving me a wider field of view and more light, and I rarely missed the extra 2X magnification of 10X42s.

As every birder knows, however, things do get tough in very dark, overcast rainforest understory conditions, challenging the abilities of almost any optics. In my equipment testing, finding binoculars that will “see through” the darkest most abysmal conditions—or the most awful gray backlit situations—requires a price jump up into the $1,000 range, not something most birders can afford. (See, for instance, this review and this one). That said, for $299.95 the Pro Issues offer solid, competitive value while boasting some additional advantages . . .

In an age when many corporations throw their weight around with little regard to the environment and social justice, Nocs offers a refreshingly positive set of values for the ethically responsible birder. The company is a member of 1% for the Planet, donating 1% of its revenue to supporting environmental organizations. It is also certified as climate neutral and is fully committed to sustainable packaging. In fact, I haven’t found a single piece of plastic packaging on any of the Nocs products I’ve received. The quality of its products also ensures that they will last long into the future, reducing the need for buying—and discarding—cheaply made equipment over and over. If your Nocs product should somehow break or fail, the company offers its “No-Matter-What Lifetime Warranty.”

All of this makes me give the Pro Issues a big thumbs up. If you’re still not convinced, I should mention that the 8X42 Pro Issues come in Ponderosa (green), Oxblood Maroon, and Marianas (blue) colors. That will ensure that in addition to having a great set of binoculars to accompany you on your birding adventures, you will be the most stylish birder anywhere in sight!

The author received no financial compensation for this review.