In our last post, we detailed where to buy bird-related books. For our 200th post (gasp), we’d like to share some of our favorite bird books. We are by no means attempting to be comprehensive and we apologize to the many fine authors and books we didn’t have space to include. When it comes to holiday shopping especially, however, we realize that “less is more” so we’ve limited ourselves to the books that first soar to mind. Note that we haven’t gone crazy on the hyper-links here, but recommend just calling your local indie bookstore and placing an order (see our last post). Any of these books can also be ordered from Buteo Books or from a certain not-to-be-named e-commerce giant. Please feel free to share this post with friends and others in desperate need of holiday gift ideas!

Field Guides

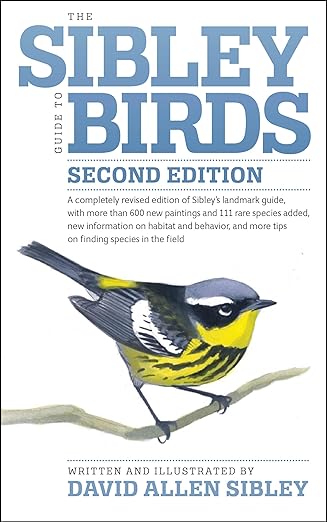

There are so many field guides available that your head will spin considering them. Braden and I have enjoyed field guides by Peterson, National Geographic, Kenn Kaufman, and many other sources. The one we return to again and again, however, is The Sibley Guide to Birds, Second Edition. While many other guides seem cramped or present information in a difficult-to-use format, Sibley strikes the right balance with generous, uncluttered illustrations and to-the-point identification information and range maps. If you’re going to buy one guide for the US and Canada, this is the one. Note that if you need field guides for specific countries or regions, you often won’t have a great deal to choose from. Our first stop is usually Princeton University Press, which seems to have field guides for many of the world’s regions (see our last post).

“How To” Guides for Beginners

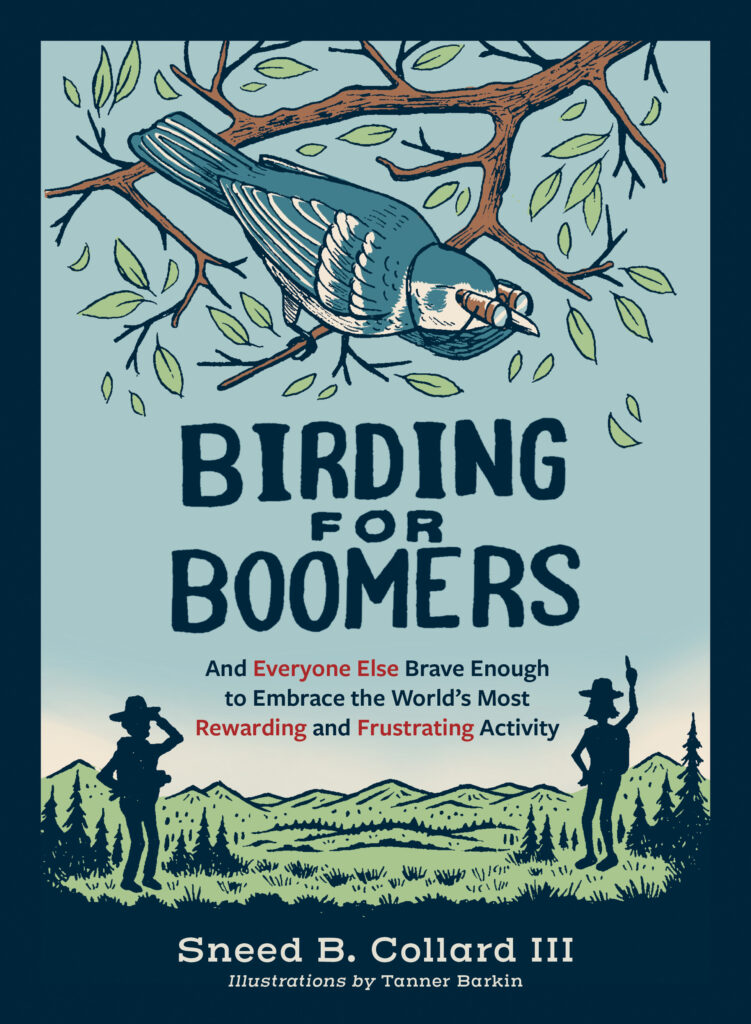

I swear, I wasn’t going to include my own book near the front here, but it logically follows field guides. Especially when it comes to buying a gift for the beginning birder, you can’t beat Birding for Boomers—And Everyone Else Brave Enough to Embrace the World’s Most Rewarding and Frustrating Activity. Here’s a recent review from Foreward Reviews: “Because the book is aimed at new birders, it includes advice about what kinds of binoculars to consider, what clothing and equipment to use, the value of a good field guidebook, and useful online resources. Its guidance is casual, often relayed with light humor and embellished by personal anecdotes. Challenges specific to boomers factor into its advice on birding with hearing, eyesight, and mobility challenges, and into its considerations for those on fixed incomes. It also makes important points about safety for nonwhite and LGBTQ+ birders. With its ranging approach and easy-to-follow advice, Birding for Boomers is a handy guide for all those—boomer or otherwise—who are looking to pick up an ornithological hobby.” Click here to order!

Birding Road Trip Books

We’re going to stick with two classics here. The first is Wild America: The Legendary Story of Two Great Naturalists on the Road by Roger Tory Peterson and James Fisher. This really is required—and enjoyable—reading for those working on a life list or doing a Big Year, or anyone wanting to educate herself on the history of birding in the United States. Our second choice is Kenn Kaufman’s irresistible Kingbird Highway: The Biggest Year in the Life of an Extreme Birder. This was one of the first birding books Braden and I read and it is still one of our favorites, recounting the passions and pursuits of someone who just couldn’t help but chase and learn about birds. If you need to add a third title to this list, we wouldn’t complain if you picked up Warblers & Woodpeckers: A Father-Son Big Year of Birding!

Natural History and Science

This category could fill several blogs, but we’ll keep it brief except to say that you must read all of the books below—and they all make great gifts for anyone remotely interested in nature.

Where Song Began: Australia’s Birds and How They Changed the World by Tim Low: highly entertaining, it will change the way you think about birds.

A Most Remarkable Creature: The Hidden life and Epic Journey of the World’s Smartest Birds of Prey by Jonathan Meiburg: a fascinating account of one of our favorite groups of birds, caracaras.

Far From Land: The Mysterious Lives of Seabirds by Michael Brooke: a wonderful account of birds most of us want to spend more time with—but, sadly, never will.

Hard to Categorize—But Read Anyway

The Ravenmaster: My Life with the Ravens at the Tower of London by Christopher Skaife. The title says it all, but doesn’t come close to reflecting just how entertaining and fascinating this book is!

Imperial Dreams: Tracking the Imperial Woodpecker Through the Wild by Tim Gallagher. This book provides a captivating blend of adventure and natural history, following a small group’s dedicated efforts to find a species that now is almost certainly extinct—but just might not be!

The Falcon Thief: A True Tale of Adventure, Treachery and the Hunt for the Perfect Bird by Joshua Hammer. A fascinating look at the world of falcon and egg poaching.

And One More for Montanans

If you really want to buy something special for your Montana birder or birding family, take the plunge on Birds of Montana by Jeffrey S. Marks, Paul Hendricks, and Daniel Casey. This remarkable volume summarizes just about everything that is known about more than 400 Montana resident, migrant, and vagrant bird species. Rarely a week goes by when we don’t dive into this book to learn about a bird we’ve seen or have been thinking about. The book occupies a prominent place on our shelves and is a prized acquisition in our bird book library. Click the image below to order.