Watch the book trailer for Border Crossings now!

If you ever doubt how inspiring birds are to people, just look at the incredible bird-related creativity writers, artists, and photographers pour forth into the world. I plead guilty to be among their ranks as birds have inspired at least half a dozen of my books and countless articles. Sometimes, though, birds themselves are not the topic. Instead, my pursuit of birds gives me another idea. Such is the case with my new picture book, Border Crossings.

During the past seven years, Braden and I have been fortunate to be able to bird along the U.S.-Mexico border at least four times: twice in Arizona, and once each in Texas and California. These trips have been among the most inspiring of our birding lives, not only providing glimpses of hundreds of remarkable birds, but introducing us to the rich human culture that spans the border region. When our former president announced plans to build a steel barrier the full length of our border, it rang alarm bells for numerous reasons. For one thing, it seemed a giant slap in the face to Mexico, a country we depend on and take advantage of in many ways. I also worried how a wall would impact the myriad animal species that regularly cross back and forth across the border.

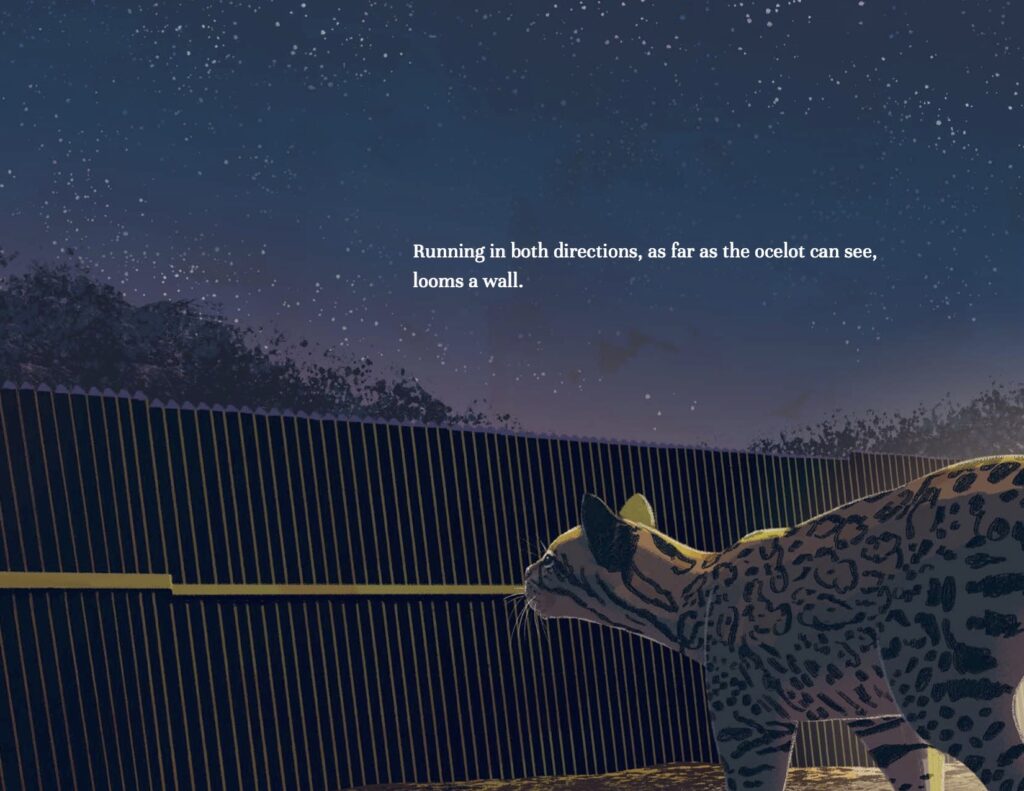

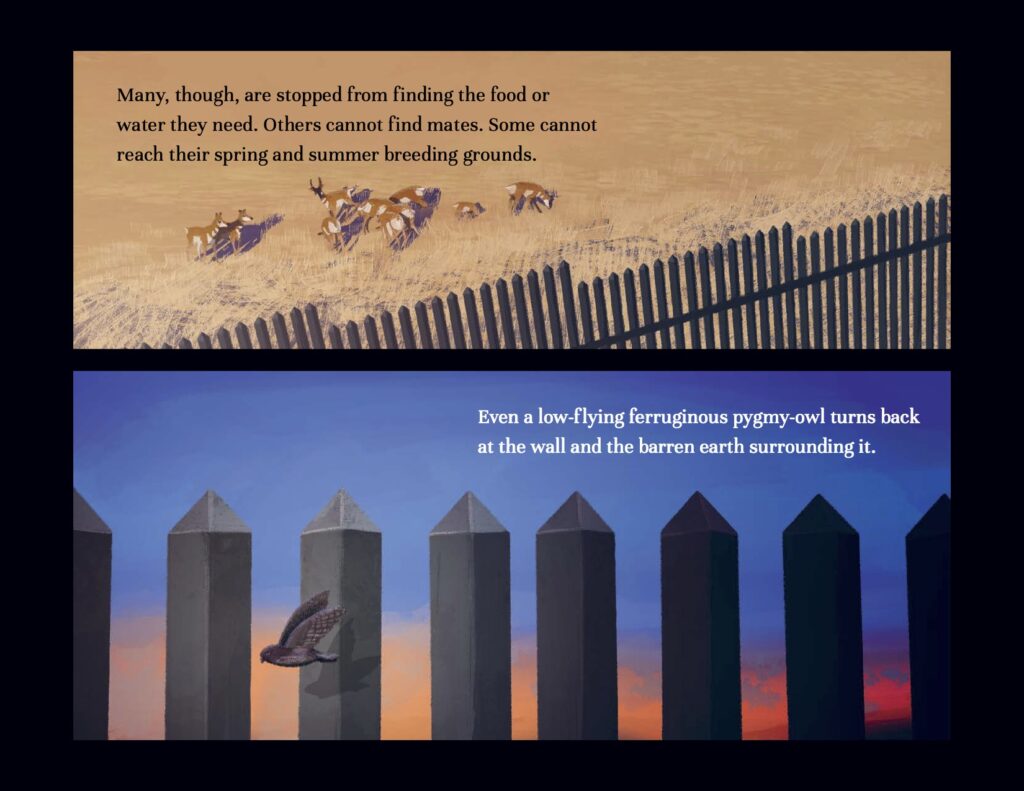

Though we humans have drawn an artificial line separating the U.S. and Mexico, the fact is that continuous ecosystems run through this remarkably biodiverse region. In these ecosystems, animals routinely cross back and forth from one country to another. Many do this in the course of their daily routines while others cross mostly during annual migrations. The steel “bollard” wall, however, has gaps only four inches wide—small enough to exclude hundreds of animal species. Even some birds—think game birds, roadrunners, and Ferruginous Pygmy-owls—probably turn back from this monstrosity. That’s not to mention javelinas, pronghorn, tortoises, hares, wolves, and dozens of other larger animals. Clearly, in their rush to build a political statement, no one in charge gave wildlife the slightest thought.

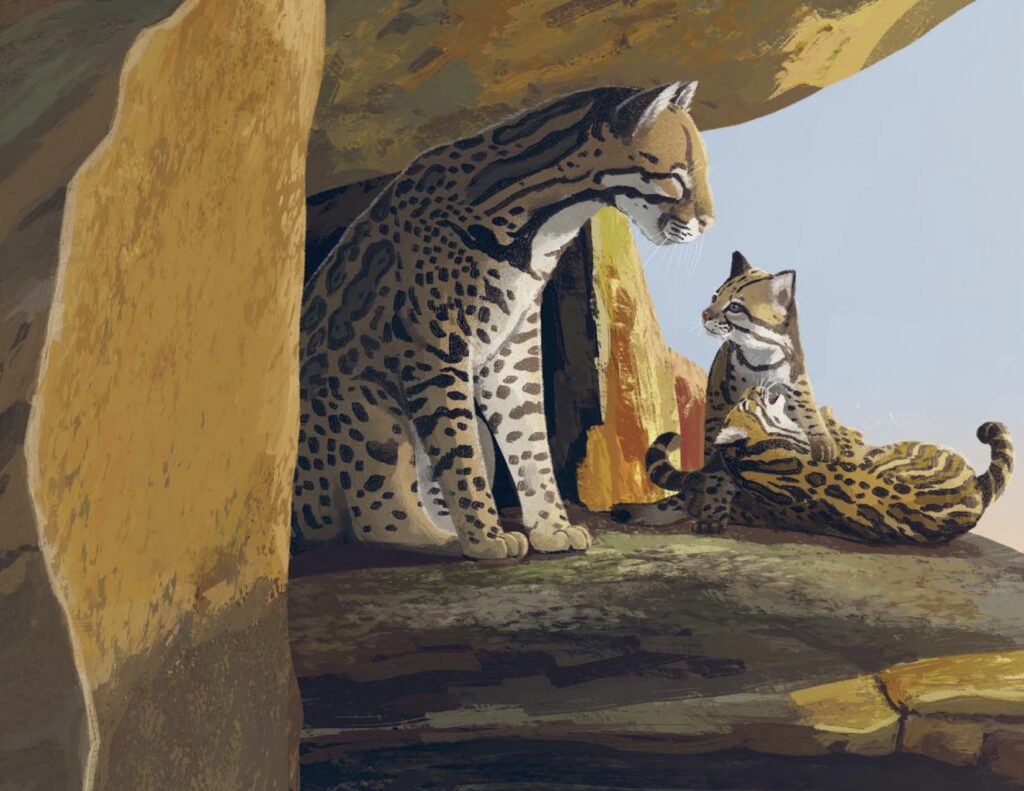

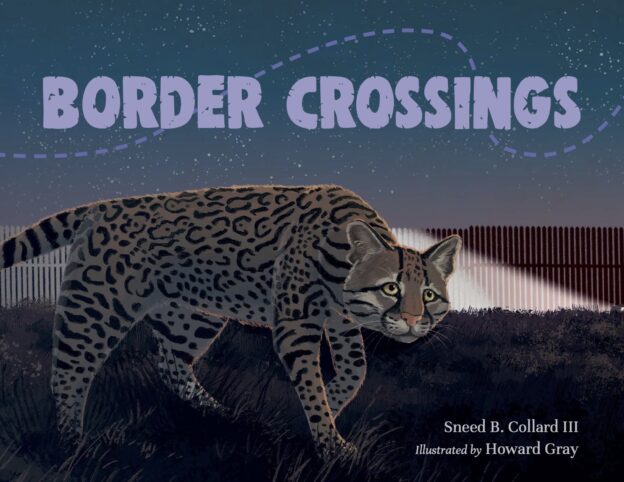

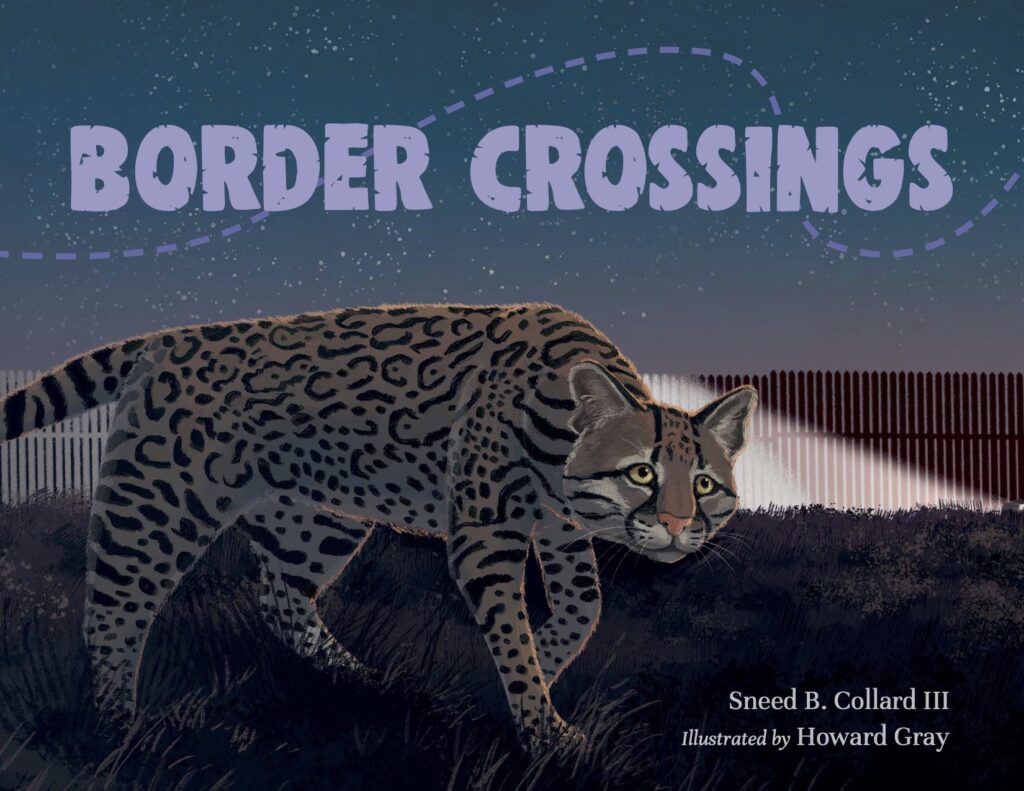

Border Crossings is my attempt to raise awareness of this important issue. To illustrate the dilemma, the story follows two ocelots. These beautiful wild cats live in both Texas and Arizona as well as Mexico, and I decided to show the plight of one that is free to cross the border without obstruction—and one that is blocked by the imposing steel barrier. I was fortunate that my publisher hired the talented Howard Gray to illustrate the book. His remarkable illustrations really bring the story to life and, I hope, make readers young and old think about the often catastrophic consequences of simple-minded solutions.

One problem I had writing the story is that wall construction proceeded at breakneck speed even as we were going through the editing process. On our last trip to Arizona, in fact, Braden and I were dismayed to see this ugly barrier stretch across several regions that had been beautifully wall-free during our previous trip in 2016. Rather than trying to rewrite the story, I explain the situation in the backmatter. Realistically, I don’t see the wall coming down anytime soon, but I hope Border Crossings will help create momentum to at least build numerous wildlife crossings through it. If you’d like to make a difference, share your concerns with your U.S. Senators and Congressmen. As great men have stated in the past, only if we stay silent can tyranny—and in this case, horrible ideas—triumph.