If you’ve been following our posts the past five years, you’ve probably learned that Braden and I like to kick off a new year with a big day of birding. Last year on January 1, we enjoyed an exceptional day, chalking up almost 50 species including Snowy, Short-eared, and Great Horned Owls. This year, we didn’t get out until January 3—and following a much colder snap of weather—and weren’t sure what we might find. I predicted we’d see 45 species while Braden opted for a more conservative 40. We both agreed, though, that we might be a bit optimistic.

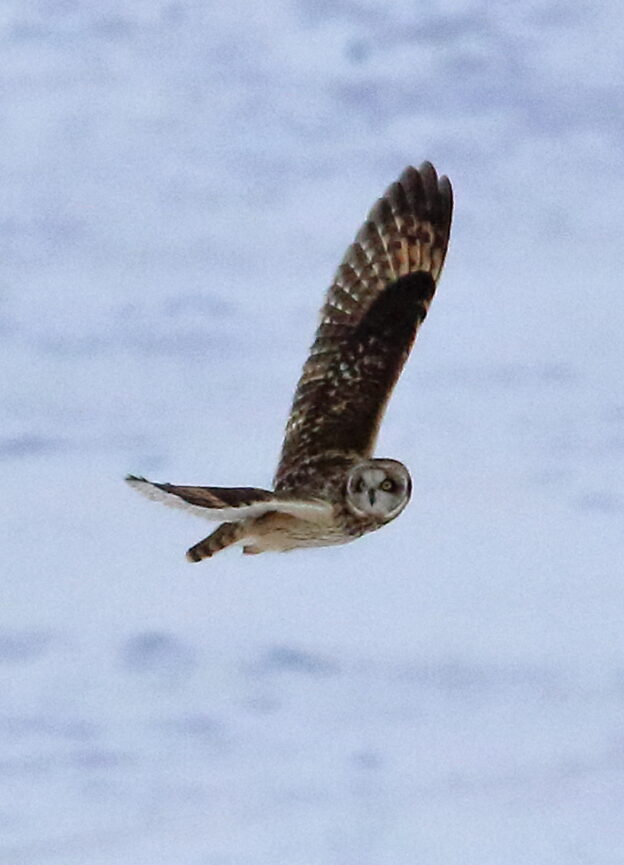

We backed out of our driveway in total darkness and an hour later, as dawn spread over the horizon, were greeted by the sheer majesty of the snow-covered Mission Mountains, surely one of the most stunning mountain ranges in the Lower 48. Our first destination? Duck Road at Ninepipe, perhaps our most reliable spot for Short-eared Owls. Alas, these owls are not to be trusted. They had obviously received advanced intel about our arrival and skedaddled to some other part of the refuge. As we crept along in the early light, though, we spotted a flock of about sixty small birds suddenly rising up from the snow-covered grass. “Waxwings?” I asked as Braden quickly got his binoculars on them. I parked the car as he answered, “No. Guess again.” “Snow Buntings?” I asked excitedly. “Yes!”

We watched the birds whirl around before landing again, and quickly broke out the spotting scope. Often, Snow Buntings travel with Lapland Longspurs, but as we scanned the birds feeding hungrily about a hundred yards away, we saw that this flock was pure buntings. Remarkably, these were the first Snow Buntings we’d ever seen on the west side of the mountains and it kicked off the day in fine fashion.

We left Ninepipe with only about ten species, but felt optimistic heading north, and sure enough, found a pair of gorgeous Long-eared Owls at a well-known spot near Polson, Montana. At a nearby bakery, we also happened to snag two donuts and a cinnamon roll for our Year List. Yum!

We weren’t sure what we were going to do next, but decided to retrace last year’s route and continue on to Kalispell in hopes of finding a Snowy Owl. Last year, we had happened into an amazing group of waterfowl at the north end of the lake, but this year we ran into a much smaller group about halfway up the west side of Flathead at Dayton Bay. Here we found Trumpeter Swans and six kinds of ducks, and it was a good thing as we discovered that the north end of the lake was almost completely frozen.

After an unsuccessful search for Snowy Owls, we stopped at Panera’s for lunch and contemplated our next move. “We could go to the Kalispell dump,” Braden suggested. I cringed at the idea since we’d been yelled at a couple of years before when trying to go there to find gulls and Gray-crowned Rosy-finches. The trick was to arrive with some trash to throw away, but we’d forgotten to bring any. As we munched away on our Kitchen Sink cookies, however, we formulated a plan. After leaving Panera’s I drove behind some of the big box stores nearby and, sure enough, found some wasted cardboard sitting there. I tossed it into our trusty minivan and we were all set!

Alas, we found nothing truly extraordinary at the landfill. We did pick up Herring Gulls, which can be a bit tricky to locate in Montana, but the real surprise was a group of about ten turkeys feeding on garbage. Hm. “I didn’t know they could do that,” Braden said, but it made sense. After all, the amount of food Americans throw away could easily feed several other countries. Though we failed to find anything really rare, we had completed our covert mission and headed south again feeling like we’d done our best. Click here for our dump checklist!

As the day again drifted toward darkness, we again hit Ninepipe on our way back to Missoula, picking up American Kestrels, a Northern Harrier, and a couple of large groups of pheasants, but no Short-eared Owls. As a consolation prize, though, as soon as we got home, Braden heard Great Horned Owls hooting from our front porch and called me out to listen. We ended the day with 35 species, undershooting even Braden’s smaller target, but felt good about the day. It was still a respectable number to start the new year, and with Braden heading back to college soon, we both cherished another day getting to bird together. How can you do better than that?