FatherSonBirding is a labor of love and Braden and I keep it advertising-free. If you’d like to support our efforts at independent journalism, please consider sharing our posts with others and purchasing one or more new copies of Sneed’s books by clicking on the book jackets to the right. Thanks for reading and keep working for birds. We will!

Not quite two years ago, I posted “Birding Glacier National Park in the Long Hot Winter of 2024.” The blog resulted from an invitation I received to speak to school kids in Browning, Montana, and I took the opportunity for some rare winter birding at my favorite park. The post has received a lot of views, either because people love Glacier or they are interested in the impacts of climate change or both. A couple of weeks ago, I was fortunate enough to be invited back to Browning. This time, I came a day early and my hosts were gracious enough to provide me with a place to stay for the extra night. My last post narrated my drive up, especially the devastating state of the drought along the Rocky Mountain Front. With my extra day to bird, though, I planned to return to Glacier and I wondered, “Would the park be as hot and dry as before?”

I woke in my East Glacier lodging well before dawn and about seven a.m. set off for my first destination, the Chief Mountain road that leads up to Waterton Lakes in Canada. As I drove toward Browning before turning north, a spectacular orange fireball rose on the eastern horizon. I’ve seen lots of sunrises in my life, but nothing matches a sunrise over the northern Great Plains. As a bonus, a red fox and young bull moose greeted me from the side of the road!

My route took me to Saint Mary and up past the one-bar town of Babb before I turned left toward Canada at about 8:30. I sadly didn’t plan to visit our northern neighbor. Today, much as I had on my last visit here, I had a particular quarry in mind: Boreal Chickadees.

As their name implies, Boreal Chickadees live mainly in northern spruce & fir forests and as such, their range barely dips into the US in a few places along our northern border. Lucky for Braden and me, Montana happens to be one of those places. We had found our first BOCHs almost by accident during covid, when Glacier had been closed and we decided to try our luck along the Chief Mountain road. To our delight, we found the little birds. Stunningly cute, their brown heads and other features closely ally them with both the Chestnut-backed and Gray-headed Chickadees, the latter now thought to be extinct in Alaska, their only known home in the US. In any case, on my visit to Browning two years ago, I had relocated BOCHs on the Chief Mountain Road, and it was my aim to do so again today.

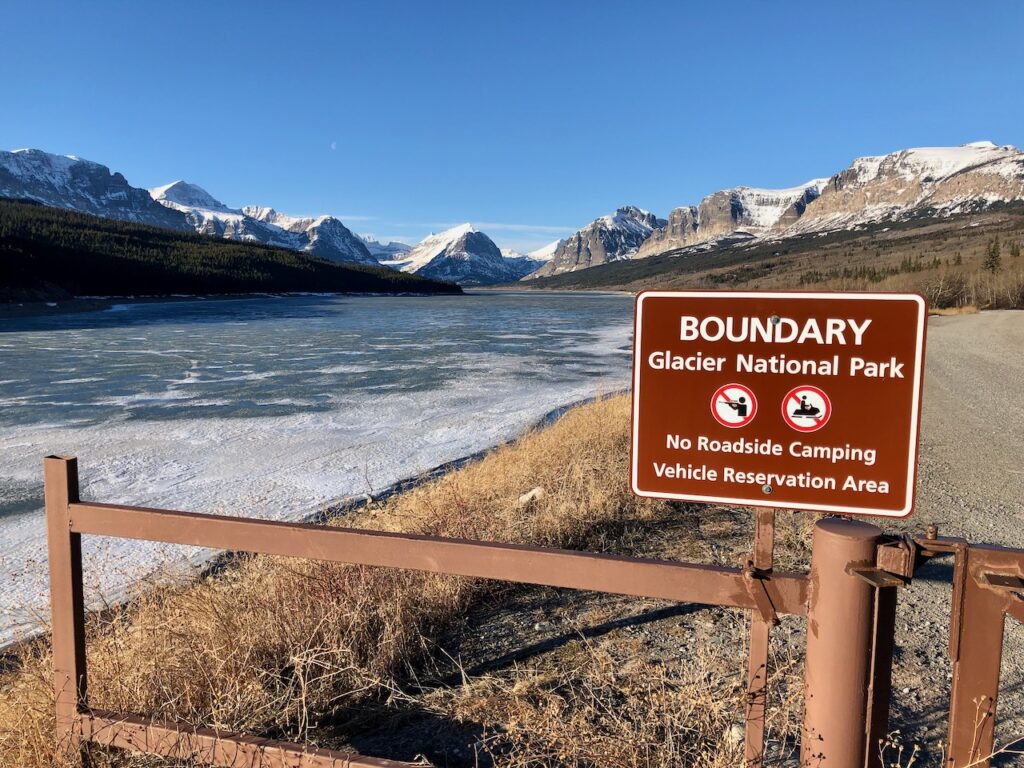

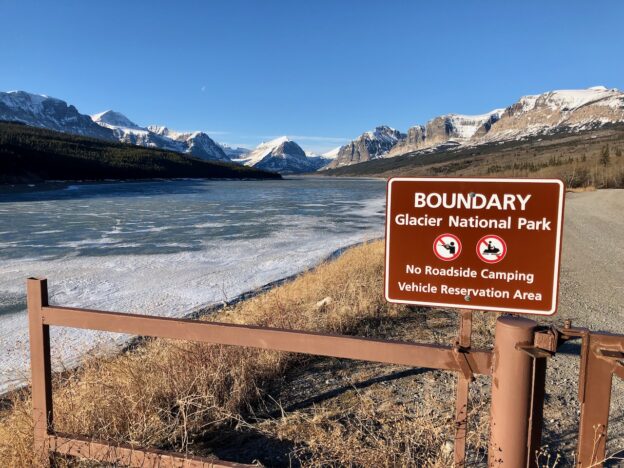

For my first try, I stopped at the pull-out right next to the Glacier National Park sign. I walked the road for a few minutes and managed to grab the attention of three Red-breasted Nuthatches while Sound ID picked up the calls of Golden-crowned Kinglets (which due to my ears, I have never been able to hear), but no chickadees.

I repeated this routine five more times along the road between the Glacier NP sign and the Canadian border. I got really excited at one point when I saw a flurry of bird activity from my car. I leaped out, binoculars and camera in hand, and saw robins, more nuthatches, and a Hairy Woodpecker. A foursome of Canada Jays, perhaps the most refined members of the corvid family, swung by to check me out. No chickadees.

As I searched, I especially looked for densely-packed spruce trees along the road, but I realized that lodgepole pine actually dominated many areas. “Hm. Maybe this isn’t a preferred location after all,” I thought. “Maybe we just got lucky the past couple of visits.”

I had started to get that “I guess I’m not going to find them” feeling when I noticed a little area that seemed to have more spruce. There was no pull-out here so I just parked as far off the road as I could and walked back to where a brushy meadow pushed westward into the forest. The meadow was lined with more spruce than anything else, and as if to lure me in, two more Canada Jays landed to be admired. “Might as well give this a try,” I thought.

I followed what appeared to be an overgrown path through waist-high shrubs. It occured to me that if berries grew nearby this would be an ideal place to get ambushed by a grizzly bear, but I cautiously pressed forward. My hopes shot up when two small birds rose out of the brush and landed in a tree. I got only a brief glimpse and still have no idea what they were, though I’m guessing some kind of sparrow.

I was approaching the end of the meadow when I saw more birds flitting around up ahead. I spotted another Red-breasted Nuthatch and Sound ID picked up White-crowned Sparrows, Golden-crowned Kinglets, and Dark-eyed Juncos. Then, suddenly, I heard chickadees—and they definitely were not Black-cappeds!

Within moments several tiny birds landed in the trees before me. It took a few tries to get eyes on one and to my joy, it was a Boreal! There were four of them altogether and wow, did they have a lot of energy! Not only were they checking me out, they were checking out every other bird, too—including a Ruby-crowned Kinglet keeping company. I managed a couple of good photos. Then, within minutes, all the birds departed—even the White-crowned Sparrows with their loud contact calls. Smiling, I traipsed back to the car. The sun had a special warmth to it and Chief Mountain rising above the forest added magic to the moment. Little did I know, however, that this wouldn’t be my last “moment” of the day.

The glow of seeing Boreal Chickadees still with me, I made my way back to Babb and turned right, up the road to the Many Glacier Valley. A large flashing sign warned that there was no general admission parking there, but I love this drive and decided to go as far as I could. I passed through groves of aspen glowing gold with fall foliage and relished the views of Mt. Wilbur and other familiar peaks ahead.

At the Lake Sherburne dam, I stopped and got out for a look at the reservoir. In keeping with my observations from my last post, it was as low as I’d ever seen it, a giant “bathtub ring” leading from the forest edge down to what water remained. I’d also noticed that Swiftcurrent Creek was incredibly low—mere rivulets flowing between a pavement of exposed rocks.

I still had plenty of time and wanted to do some kind of hike in the park, so I returned to St. Mary and found myself on a little trail for the Beaver Pond Loop. In all my visits to Glacier, I’d never before done any hiking or walking near St. Mary so I set out on this path with some excitement. It wasn’t the most dramatic hike, hugging the south side of St. Mary Lake, but it offered terrific views up the valley and the blue sky and warm (too warm) conditions made for pleasant hiking.

I’d walked maybe a quarter mile when I rounded a bend to see a dark object ahead next to the trail. At first I thought it might be a hare or other mammal. When I raised my binoculars, I realized with astonishment that it was a grouse. Not only that, I felt pretty sure it was a Spruce Grouse!

If you’ve followed FatherSonBirding, you’ll know that I’ve seen SPGR only twice (see posts “Gambling on a Grouse-fecta” and “August: It’s Just Weird”), and had gone to great effort to do so. To have one just show up unexpectedly, well, that pretty much blew my mind. Still, I didn’t feel 100% sure on the ID, so I snapped some quick photos to send to Braden. Then, the grouse started walking toward me. “Whaaaaat?” I wondered.

That’s when I realized that another hiker stood on the other side of the bird and had herded it my way. Finally, the grouse wandered off into the forest, leaving me both astonished and gratified. I guess I had put in enough grouse effort to finally be rewarded by such encounters!

I continued onto a nice rocky beach on St. Mary Lake and found a perfect rock for sitting. Two pairs of Horned Grebes played and fished out on the water—my best look at this species all year—and I relished a few moments in one of earth’s most spectacular places.

Glacier, though, doesn’t exist by accident. It’s here because forward-thinking people planned for the future long ago. As the epically dry conditions of this part of the world attest, we need to keep thinking forward if we want our children and their descendants to have such places to cherish. As I said in my last post, all of us need to fight the disinformation and greed of climate deniers however we can. Whether that’s by making a donation to an environmental or legal group battling the horrible policies of the current administration or making changes to lower your own carbon footprints, every effort matters. Now, more than ever, is the time.