Our thoughts go to all of the Californians getting hammered by unprecedented rains right now, and we hope that you are all staying safe—and preferably indoors. While the Southwest is getting one historic climate event, Montana has been getting another: record heat and dryness. Both of these add a heightened sense of urgency to tackling climate change by reducing greenhouse emissions and promoting renewable energy. And, of course, these events are certainly impacting birds. Last week, I had a chance to explore one of our nation’s most pristine areas to see what the birds are doing.

Even before I moved to Montana in 1996, I had visions of visiting the Many Glacier Valley in the depths of winter. In college, I had spent the best summer of my life working as a cook at Swiftcurrent Motor Lodge, and had returned to the valley many times since then—but never in our darkest, coldest season. What would this wonderland be like covered in snow and ice? Last week, almost fifty years after working there, I got a chance to find out. The only thing missing? Winter itself.

I had been invited to spend four days visiting with pre-K through grade 1 students in Browning, Montana, a trip I looked forward to for many reasons, including the chance to learn more about Blackfeet culture and explore the area. As a bonus, I would be working mainly in the afternoons, freeing up the mornings for birding and other activities. As the librarian and I put together the trip, however, I never imagined that I would be visiting during an unprecedentedly warm winter in which temperatures were breaking records daily and the landscape stood almost devoid of snow.

On the drive to Browning, I stopped at the Freezeout Lake wetlands complex near Great Falls and counted several thousand Canada Geese and Mallards. To my surprise, the geese were flagged as rare on eBird for this time of year. Why? Because the lakes are almost always frozen in January and February, but this year large areas of open water shimmered, inviting both geese and ducks.

Reaching the outskirts of Browning, I turned right for a side trip to Cut Bank. In a normal winter, this entire area would be covered in snow, providing a chance to find Snowy Owls, Snow Buntings, and other typical winter birds. Not today. Driving mud and gravel back roads, I was lucky to find a solitary Rough-legged Hawk on a telephone pole. I did flush one group of 15 smaller birds that I assume were Horned Larks, but nothing else of note. In fact, the main birds I was seeing were the stalwart ravens, magpies, House Sparrows, starlings, and pigeons.

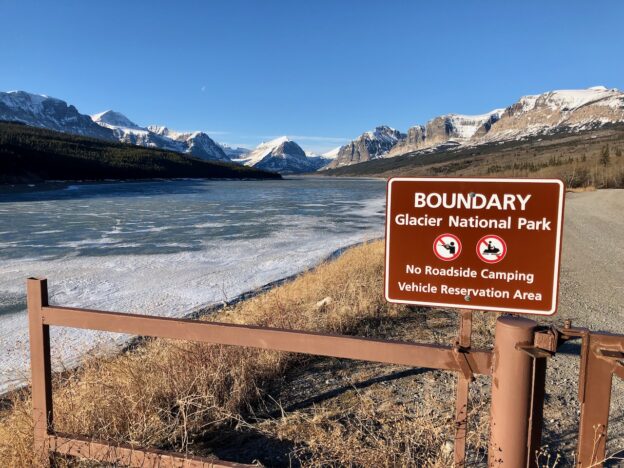

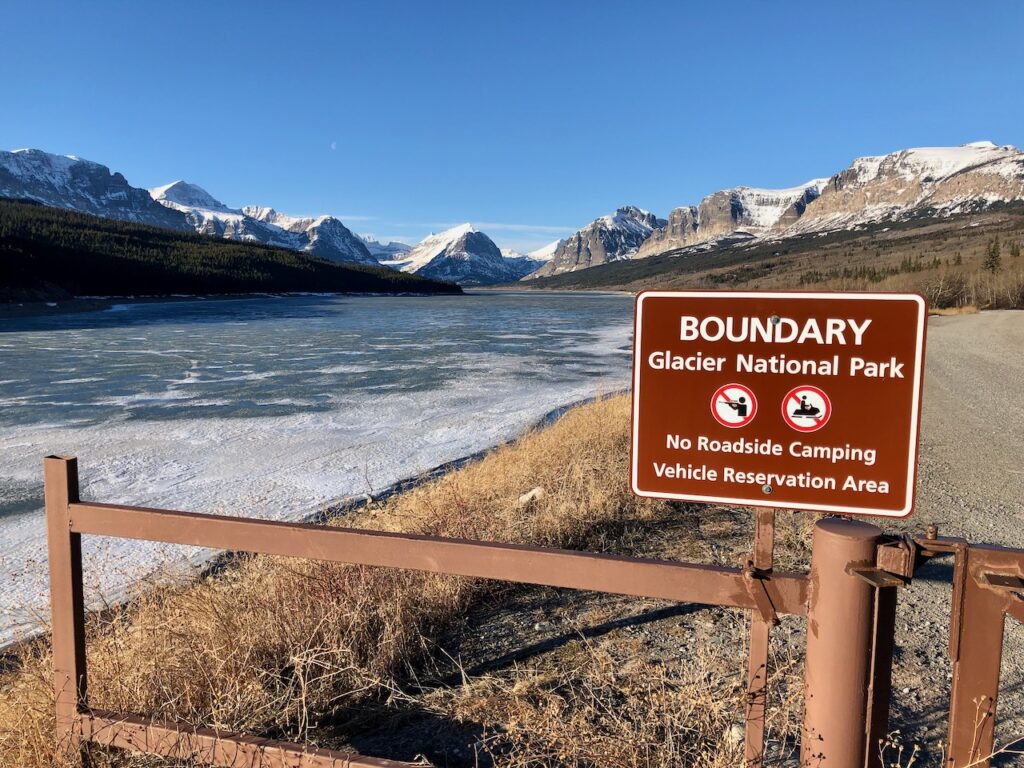

When Thursday rolled around, my birding hopes rose as I got up early and drove toward Babb, the entrance to the Many Glacier Valley on the east side of Glacier National Park. I had no idea how much of the road was open, but made it to the park boundary at Lake (reservoir) Sherburne dam. There, I parked and donned my camera and binoculars.

I couldn’t have asked for a more astonishing day. By 9:00 a.m., temps had reached into the mid-30s and were rising rapidly. Despite an extremely dry winter, a thin layer of snow covered the spectacular peaks of the continental divide and full sunlight created an unparalleled, dazzling landscape. As an extra “cherry,” a waning gibbous moon slowly sank toward 9,300-foot Mount Allen. I paused to take a deep breath and appreciate that I was probably the only person on earth observing this incredible scene. Then, I set out.

A raven greeted me as I stepped into the park, but I wondered if I would see any other animals. Would a grizzly bear be taking a mid-winter stroll on a day this warm? I didn’t know, but spotted no other critter as I walked half a mile along the reservoir. I didn’t have a great deal of time, so I turned around after 20 minutes, and as the day continued to warm, a few birds made an appearance. I heard Black-capped Chickadees and a woodpecker drumming in the distance. Then, a grouse burst out of some stunted aspen trees to my left. I desperately watched it flying away, looking for any ID clues, but alas, I just don’t know grouse well enough to be sure. The bird was gray, however, and the habitat was wrong for Ruffed and Spruce Grouse, rendering a 95% probability of Dusky Grouse, but since I wasn’t sure, I didn’t record it on eBird.

Despite the incredible scenery, I was feeling a bit thwarted bird-wise, and calculated that I had time for another hour of exploration, so I drove back out to Babb, turned left, and then left again on the road leading to the Canadian border and Waterton Lakes National Park. My mission? To find Boreal Chickadees! In fact, I was driving the very road where Braden and I had discovered our lifer BOCHs three years before (see post “Are you ready for . . . the QUACH?”). That had been during early covid days when hardly a soul traveled the road. Would I be able to find any birds today?

The road wound its way up through scenic pastures and aspen groves, climbing steadily until it reached conifers—all under the magnificent gaze of Chief Mountain. As before, I passed not a car along the way. I pulled over twice and played the calls of Boreal Chickadees, but no bird responded. Then, I actually saw a flock of chickadees up ahead and eagerly braked to a halt.

Not BOCHs. Instead, a mixed flock of Mountain and Black-capped Chickadees, with a Red-breasted Nuthatch joining them.

Undeterred, I continued, and soon stopped for another flock of Black-cappeds. I wondered how much exploring I had time for, but passed a Border Patrol truck and soon was forced to stop at the closed boundary of Glacier National Park. Turning around, I again parked to play a BOCH call with no luck. The Border Patrol truck approached and the agent rolled down his window for a chat. I told him what I was looking for and asked him if he saw many birds along this stretch. “Some Stellar’s Jays,” he answered, “but not a lot else.”

I wished him a good day and continued driving back toward Babb. Before the road began descending again, a large pull-out opened up on the left and I stopped one last time. Not expecting much, I played a BOCH song and made some pishing noises. Within moments, six chickadees surrounded me! Boreal Chickadees!

The chickadees were much more curious about me than their congeners (animals in the same scientific genus, i.e. the Black-capped and Mountain Chickadees). The Boreal Chickadees flew back and forth above me and called from nearby branches. I even nabbed some decent photos. I spent ten or fifteen minutes with them, barely believing I was having such a great experience with these elusive, high-altitude and high-latitude songbirds. It once again renewed my appreciation for living and birding in Montana, since this region is one of the few places this species dips into the United States from its main distribution in Canada.

Feeling satisfied and grateful for such a marvellous morning, I headed back to Browning, spotting only a few ravens and Rough-legged Hawks along the way. No matter. The BOCHs and breathtaking views of the Many Glacier Valley had made this a day I would never forget. Now if we can only get some snow.